De-risking automated decisions: Guidelines for AI governance

At the 2022 All-Actuaries Summit, Chris Dolman, alongside Tiberio Caetano, Jenny Davis, Simon O’Callaghan and Kimberlee Weatherall, presented joint work on the topic of artificial intelligence (AI) governance, summarised in this article.

|

You can find more detail in the full research paper published by Gradient Institute, and supported by the Minderoo Foundation.

|

As we outlined at the Summit, the question of how to manage the risks of AI failure has taken off over the last few years, in response to repeated issues arising from AI systems all over the world. In considering AI failure, many sub-fields have emerged, such as fairness, transparency and interpretability.

However, the overarching concept of AI governance is too frequently overlooked. While many regulators, standards agencies and lawmaking bodies are considering this topic, this work is nascent. For organisations deploying AI systems today, this leaves a gap – what should be done, today, to ensure AI systems are governed appropriately?

It is this gap that our paper seeks to address. We make three contributions:

- We explain the control and monitoring gaps that emerge when human decisions are replaced by AI.

- We identify a non-exhaustive set of risks introduced or amplified by these gaps, inspired and illustrated by real case studies.

- We suggest a non-exhaustive series of actions to address the risks, regardless of perceived risk levels.

We suggest that practitioners take our work as a starting point, to be adapted to the needs of their organisation and the specific AI systems it seeks to implement.

Control and monitoring gaps

When traditional human systems are automated, typical control and monitoring routines – designed for human systems – may be found wanting. Our paper Identifies a series of control and monitoring gaps that can emerge. Examples of both are listed below.

Control Gaps:

- Management may be unused to specifying goals and constraints with the precision required for an AI system, which lacks common sense.

- Management may not have sufficient technical knowledge to effectively instruct their AI development team.

- AI developers may misunderstand the business domain, leading to poor translation of management’s instructions into the design of the AI system.

- While frontline humans have ‘common sense’ and can react appropriately to unexpected or subtle customer situations, AI systems may not react appropriately.

- AI systems lack discretion which many frontline humans will be able to use to improve customer interactions.

Monitoring Gaps:

- The rules of customer engagement are no longer written directly by management and may be uninterpretable to a human.

- Front line systems may make decisions affecting individual customers which are not able to be suitably explained.

- AI developers may be unable to effectively communicate upwards, due to knowledge gaps.

- Frontline humans naturally monitor interactions with customers as they occur and can adapt appropriately based on subtle cues and human empathy. AI systems will tend to lack this capacity.

- AI systems base decisions only on the data collected, without seeing a human behind the data. Their approximation of reality is crude, which may miss crucial information a person would collect.

Risks

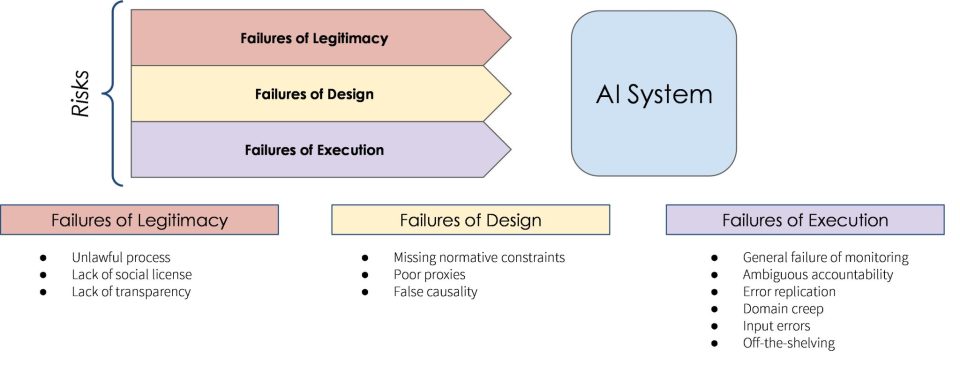

The gaps in monitoring and control outlined above challenge traditional corporate governance methods and give rise to governance risks which we as depict below. These risks are best characterised as unfortunate side-effects arising from AI deployment, not risks consciously taken in pursuit of some goal. Where it is cost-effective to do so, management of such risks is advisable.

We categorise the risks into three modes of failure:

- Failures of Legitimacy occur when an authority uses its power in a manner that is deemed socially unacceptable. This includes failure to abide by the law, but goes beyond that, observing that it may be possible to perform actions that are legal, but still fail the so-called ‘pub-test’.

- Failures of Design arise as we attempt to translate a legitimate intent into the precise mathematical language of AI software. People commonly fail to adequately specify normative constraints, use inappropriate proxies, and may ascribe causality inappropriately. Each of these risks can cause catastrophic failures of AI systems.

- Failures of Execution may occur even for legitimate, well designed AI systems as they are brought into production. The risks we discuss are more operational in nature; some are more particular to AI systems, whereas others may be contained in some related form in typical operational risk procedures that organisations may have in place.

Actions

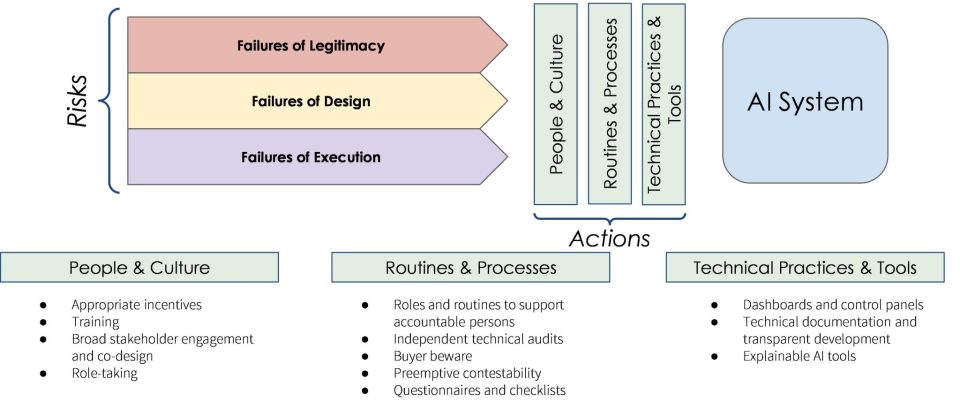

In light of the risks identified, we then proposed a series of actions for organisations to consider, as depicted below.

Again, we group our suggestions under three headings:

- People and Culture refers to actions centred on the people operating with organisations, their incentives, training, and engagement with various stakeholders.

- Routines and Processes create standardisation and norms for an organisation, to ensure that risks are appropriately and fully considered each time they are encountered. We suggest a range of routines and methodologies which can be adapted to suit an organisation’s needs.

- Technical Practices and Tools are essential to this domain, ensuring that risks of a technical nature have suitably technically informed solutions. The practices we propose should support other risk-reduction mechanisms.

Summary

Many organisations are struggling with AI governance, today, but substantial guidance on AI governance is still lacking. Our report aims to remedy this. We identify governance gaps created by the introduction of AI systems, translate these gaps into risks, and suggest actions to mitigate those risks. Clearly, our analysis is general in nature, and must be adapted to the nature, scale and needs of any organisation – we encourage people to take our work as a solid starting point to build upon in their organisation.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.