Actuaries and sustainability

Social, economic and financial systems are increasingly being affected by environmental and societal risks, and by government measures taken to try to deal with these risks. As these risks increase, so does the likelihood and expected future impact of changes and government measures.

As actuaries are long-term risk managers, these developments are critical to our understanding. Climate and Sustainability Working Group (CSWG) – previously known as the Climate Risk Working Group (CRWG) works to identify the implications of environmental, sustainability and government (ESG) risks for actuaries and help develop appropriate responses for their clients.

Very important amongst sustainability risks is climate change, which is an existential threat to the social, economic and financial systems we rely on. Other sustainability impacts on actuarial work include:

- Environmental changes and resource limitations, which have implications for prices, economic growth, investment returns and liability reserving across all practice areas.

- The trend for businesses to be held to a higher social standard than previously.

-

The expectation that businesses should contribute to broader societal objectives that recognise the importance of health, education, poverty reduction, the natural environment (embodied in concepts such as a ‘social license to operate’ or ‘stakeholder capitalism’).

In this two-part article series we run through:

- Sustainability 101: Foundations of sustainability.

- Sustainability 102: An overview of measures being taken by regulators and governments to try to deal with sustainability.

What is sustainability?

The UN defines sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.[1]” As humans, needs include:

- A sound environment.

- A just society; and

- A healthy economy[2].

Environment, society and economy are commonly referred to as the ‘three pillars of sustainability’. This definition emphasises the global, multi-faceted, long-term, and intergenerational nature of sustainability.

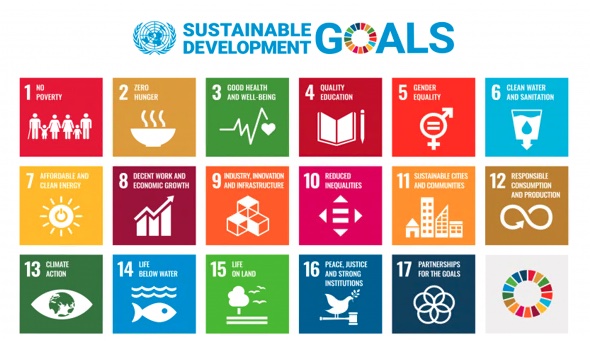

Climate risk is just one aspect of wider sustainability issues in which actuaries are already heavily involved. The UN Sustainable Development Goals[3] (SDGs), summarised in the figure below, encompass multiple aspects of sustainability including economic vitality, gender equality, human rights and disability, in addition to climate change and disaster risk reduction.

Various targets have been set under each of the 17 SDGs. Here are some examples:

| SDG | Goals |

| Goal 3: Good health and wellbeing[4]

|

|

|

Goal 5: Gender equality[5] |

|

Interested readers can find detailed facts, figures and targets for each of the 17 goals on the Take Action for Sustainable Development Goals website.

How we got here: The foundations of sustainability

Sustainability is not a new concept. In 1972, the UN conference on the Human Environment noted that people in the world have a right to access “adequate food, safe water, fuel to cook and warm themselves and sound housing”. But as far back as 1972 it was also recognized that “a stage has been reached when, through the rapid acceleration of science and technology, man has acquired the power to transform his environment in countless ways and on an unprecedented scale.”[6]

Over the second half of the 20th-century economic growth led to marked improvements in living standards. However, it was mostly achieved in ways that were ultimately globally damaging. For example, growth was achieved by:

- Extracting and burning fossil fuels to produce energy, leading to anthropogenic global warming.

- Using increasing amounts of raw materials, energy and chemicals.

- The creation of pollution that is still not adequately accounted for in the costs of goods and services.

- Exploitation of some individuals and communities (i.e. modern slavery).

These trends have had unforeseen effects on the environment, including global and regional biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation, and harmful climate change. In other words, the growth was not achieved in a sustainable way.

Managing sustainability as a wicked problem

A ‘wicked problem’[7] in social policy is a social or cultural problem that is complex and difficult to solve because of incomplete, contradictory and changing requirements. They usually involve multiple stakeholders, involve a large economic burden, and feature interconnected issues.

These are some of the barriers that feature in sustainability-related problems

- Economic externalities and the tragedy of the commons: Resources, such as land, air or water, that are owned by a group rather than privately owned are often degraded when the costs associated with their use are not borne by the person who uses them. In economic terms this effect is termed a ‘negative externality’. The tragedy of the commons is enabled by economic measures and policies which fail to account for externalities.

- Intergenerational effects: Society may be presented with the choice to pay the costs today for benefits that may not be fully realised for decades. In these types of situations, traditional cost-benefit analysis and discounting approaches tend to favour inaction, because benefits are heavily discounted relative to costs. Use of a ‘social discount rate’ partly addresses this problem.

- Interconnected systems: The three pillars of sustainability (environment, society and economy) are deeply interconnected. Systems thinking is concerned with relationships between parts and wholes rather than looking at discrete problems in isolation and is considered an ideal framework for approaching sustainability problems.

How can individuals live more sustainability?

There are many ways individuals can live a more sustainable lifestyle. Here are a few ideas[8]:

| Lifestyle domain | Example of actions |

| Food |

|

| Mobility |

|

| Consumer goods |

|

| Housing |

|

| Leisure |

|

Sustainability is a topic of focus that affects the future of the planet. This article has addressed some of the ways in which we as actuaries can contribute to managing climate risk and wider sustainability considerations from both a professional and a personal perspective. We encourage interested readers to engage in discussion and provide suggestions to help shape future CSWG activities. You can find out more about CSWG here.

References

[1] United Nations Brundtland Commission, 1987

[2] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

[3] https://www.un.org/en/sustainable-development-goals

[4] Goal 3: Good health and well-being | Joint SDG Fund

[5] Gender equality – The Global Goals

[6] https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/NL7/300/05/IMG/NL730005.pdf?OpenElement

[7] Rittel, H & Webber, M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning https://web.archive.org/web/20070930021510/http://www.uctc.net/mwebber/Rittel+Webber+Dilemmas+General_Theory_of_Planning.pdf

[8] UN Environment Programme, Sustainable Lifestyles: Options and Opportunities https://www.unep.org/resources/toolkits-manuals-and-guides/sustainable-lifestyles-options-and-opportunitie

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.