Post-Budget economic briefing outlines opportunities and risks during high inflation

Secretary to the Treasury, Dr Steven Kennedy PSM, has given a post-Budget economic briefing to the Australian Business Economists, outlining recent economic developments, the surge of inflation, and shocks to global and domestic economies.

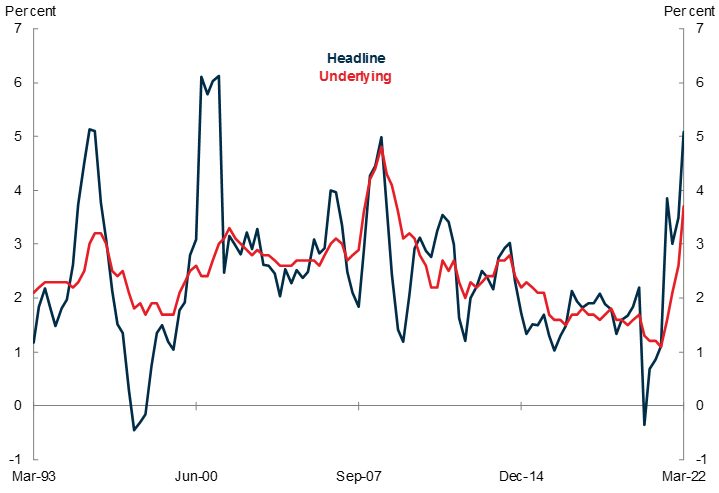

Dr Kennedy outlined the significant surge in inflation since the last release of the Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO) in April.

With headline inflation reaching 5.1% in the March quarter of 2022, it was the highest rate of inflation in more than two decades. Dr Kennedy said other developed countries are seeing even higher rates.

“For example, the latest outcomes were 8.3% for the US, 9.0% for the UK and 6.9%for New Zealand,” he said.

“Price increases are reflecting a range of shocks, some temporary and some more persistent. The interaction of these shocks is making the job of understanding and forecasting inflation particularly difficult.”

Figure 1: Headline vs Underlying Inflation in Australia

| Note: The measure of underlying inflation is trimmed mean inflation. |

A shock to the system

Dr Kennedy said there are a few culprits behind the surge. The first is the pandemic which has generated elevated global demand for goods and strained global supply chains. The second shock comes out of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“[The war has] generated a sharp increase in oil, energy, and food prices. Russia accounts for 18% of global gas and 12% of global oil supply. Together Russia and Ukraine account for around one quarter of global trade in wheat,” Dr Kennedy said.

“The disruption caused to the supply of these commodities has a direct effect on inflation through higher fuel, energy, and food prices for households, and an indirect effect through higher energy and transportation costs.”

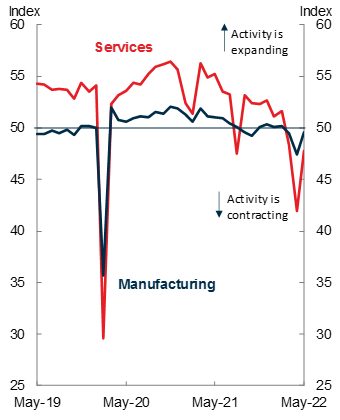

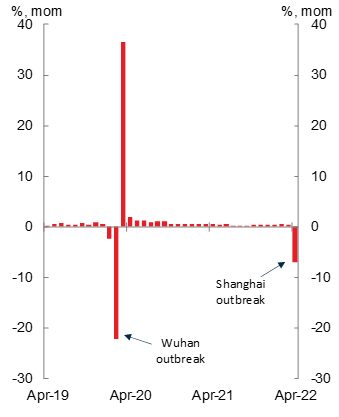

The third shock is the COVID-19 situation in China which has disrupted their economy with recent lockdowns placing pressure on global supply chains.

Figure 2: China Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI)

|

Figure 3: Industrial production in China

|

Contributors to local and global inflation

Dr Kennedy walked through the current situation around inflation showing how a combination of the shocks are interacting with capacity constraints.

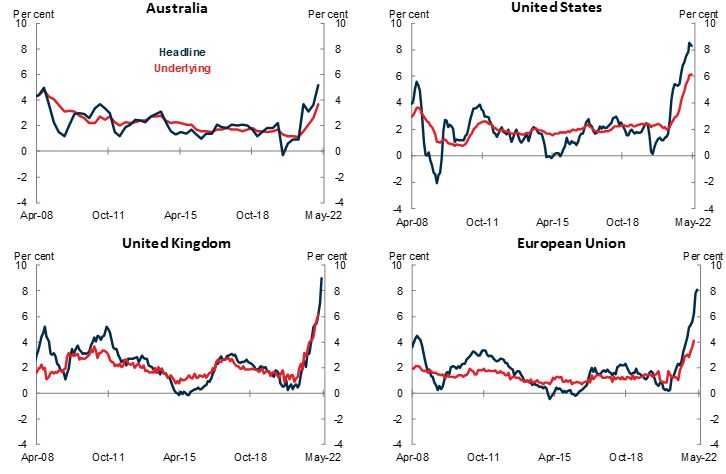

In the US and the UK, headline and underlying inflation are strengthening. While in the EU, where demand is weaker, underlying inflation has not strengthened to the same degree as headline inflation.

“The potential for policy mistakes and significant slowdowns is increasing in countries where shocks and capacity constraints are most acute,” Dr Kennedy said.

Figure 4: Headline vs Underlying Inflation comparison

| Note: Underlying inflation is trimmed mean inflation for Australia and the United States and core inflation for United Kingdom and European Union. Core inflation excludes energy, food, alcohol and tobacco. |

The situation in Australia wasn’t as dire, with headline inflation not as high as some countries due to global shocks having a smaller impact to date.

“We are probably not exceeding capacity constraints to the same extent as some other countries,” he said.

Despite weathering the storm better than others, Dr Kennedy said inflation is likely to rise above 6% in Australia, potentially higher, and remain there for the rest of this year.

COVID absenteeism, unemployment, and the labour market

Dr Kennedy touched on the continuing impacts of COVID‑19 on the economy with workforce absenteeism increasing in April. While levels remain below January levels, Dr Kennedy said it is expected to persist at an elevated level across the next few months.

“As in other countries, these shocks are hitting the Australian economy at a time when for the first time in decades it is operating near full capacity,” Dr Kennedy said.

The unemployment rate declined to 3.9% in March, its lowest level since the 1970s.

Dr Kennedy said while the labour market has tightened, recent research has suggested that some spare capacity remains.

“[This is] due to elevated underemployment levels and further scope for an increase in the labour force participation rate,” he said.

Dr Kennedy said the unemployment rate was expected to decline to 3¾ % and stabilise there until 2024‑25 and then steadily transition towards Treasury’s current assumption of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) of 4¼%.

“If realised, this forecast implies that the economy would be operating at beyond full employment for some years. In this environment, we would expect demand-side inflationary and wage pressure to be building,” he said.

“Just as fiscal and monetary policy worked together to respond to the pandemic, they will need to work together in managing the risks to inflation and the economy more broadly.

“Interest rates are at near-record low levels and therefore highly accommodative and should normalise, given the strong level of demand across the economy and the tight labour market.”

The fiscal outlook

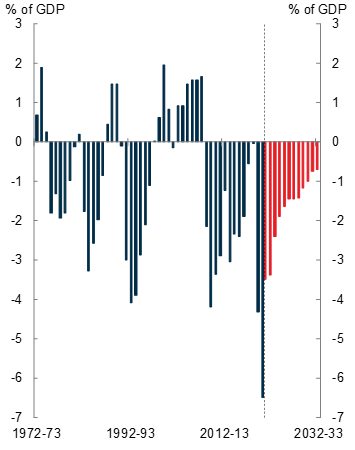

As temporary economic support measures end, Dr Kennedy said the budget balance is expected to improve over the coming years. But with significant medium-term spending pressures having emerged over the past two years, we may see spending remain at a higher level than pre-COVID.

“Having peaked at 6.5% of GDP in 2020-21, the underlying cash deficit was expected in the PEFO to shrink to 3.4% of GDP in 2022-23, and then to 1.6% of GDP in 2025-26,” he said.

Figure 5: Underlying cash balance

|

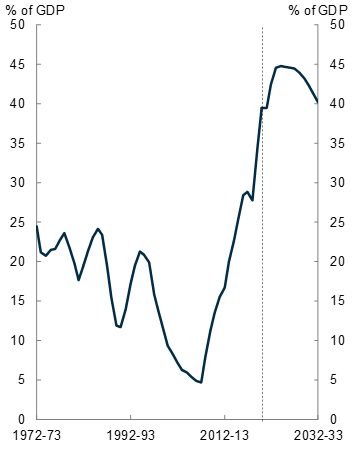

Figure 6: Commonwealth gross debt

|

“Economic downturns have tended to occur roughly every 10 years. Australia needs to rebuild fiscal buffers to ensure the Government can respond effectively to future crises. This will help to keep debt on a sustainable path over the longer term.”

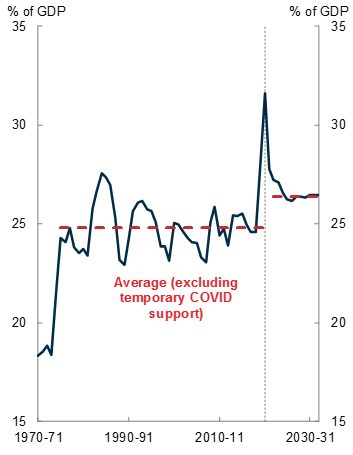

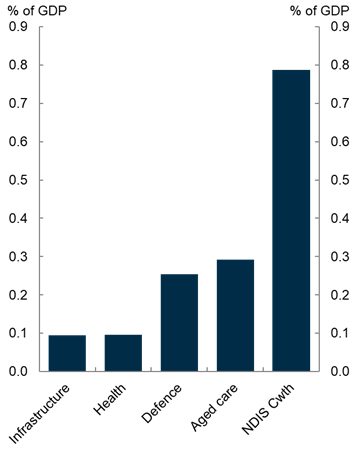

Long-term challenges: structural spending, personal income tax receipts, and productivity

Dr Kennedy then looked into the long-term challenges for the budget, starting with structural spending.

“Excluding temporary direct COVID-19 support, payments as a share of GDP are expected to average 26.4% over the decade ahead, compared with 24.8 % in the decades prior to the pandemic (charts below),” he said.

Figure 7: Government payments

|

Figure 8: Change in payments between 2018‑19 and 2025-26

|

Dr Kennedy outlined two ways to fund payment commitments: by government identifying structural savings in the budget and by raising additional tax revenues.

Another challenge we faced was personal income tax receipts. Dr Kennedy said the improvement in the budget balance in the medium term relies largely on increases in receipts from personal income taxes.

“Inflation and real wages growth will result in higher average personal tax rates over time. Unless other taxes or revenues increase, there is little prospect of having sufficient fiscal space to give this back to taxpayers in the form of tax cuts,” he said.

“This would see average personal tax rates increase towards record levels, increasing the fiscal burden on wage and salary earners.”

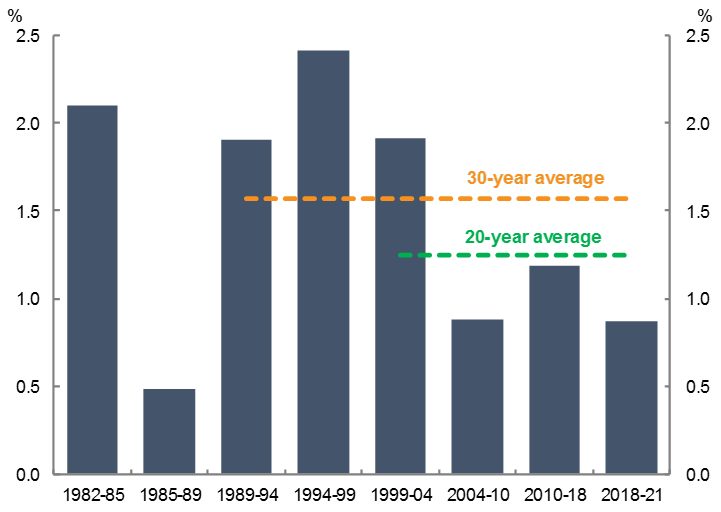

Dr Kennedy also outlined productivity as a major challenge, with growth slowing during the past 20 years and averaging around 1.2% during that period.

Dr Kennedy compared the level of productivity in Australia with the US, which has experienced lower productivity growth compared with their long-term average.

“Previous periods of domestic reform in the 1980s and 1990s were followed by periods of strong productivity growth. Such reforms appear successful in bringing labour productivity in Australia closer to US levels,” he said.

Dr Kennedy said Australian domestic policy can help adopt innovations through incentivisation and investment. This includes investment in human capital to ensure the Australian workforce has the necessary skills to access frontier technologies and methods.

“If we were able to lift productivity growth and move closer to the global frontier, that would lead to a permanent lift in the level of income and higher living standards,” he said.

Figure 9: Average labour productivity growth by cycle

| Note: The 2018-21 cycle is incomplete. |

Overcoming the challenges

Dr Kennedy ended his speech with sobering messages describing the shift he is seeing as being “made even more difficult by the most complex international environment in 70 years”.

With the war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 crisis in China, and persistent supply chain challenges, he said there are no upsides to global growth.

Combined with emerging inflationary pressures, rising electricity prices, high costs in disability support and aged care, and weak wage growth meant the tax system is coming under a lot of pressure.

But Dr Kennedy said it wasn’t all bad news.

“A challenging set of issues no doubt. There is some good news,” he said. “Australia has the lowest unemployment rate in nearly five decades and the lowest underemployment rate in over a decade.”

“The challenge now is to keep it at these levels and there are many actions we can take to improve outcomes.”

Dr Kennedy said having a tax system fit for purpose to pay for these services, that appropriately balances fairness and efficiency, is achievable.

“By improving the quality and efficiency of government services and steadily improving our regulatory systems we can contribute substantially to productivity growth,” he said.

“And there are few countries in the world with the natural advantages that we have in meeting our climate change goals.”

| You can read the full transcript on the Treasury website. |

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.