Here comes the rain again

Recent extreme rainfall across eastern Australia, and questions about the accuracy of weather and flood forecasts, offer a timely reminder to actuaries of the importance of understanding how our advice will be used, and communicating uncertainty.

Watching the extreme weather events unfold over the past few weeks, many have wondered if our weather forecasts are good enough, or if with more investment, we could do better. People made choices based on weather and flood forecasts, and for some people, those predictions have proved tragically wrong.

The Brisbane River flood peak on Monday 28 February is just one example I followed closely. It peaked at 3.85 metres on the morning high tide, but the predicted peak had changed at least three times throughout the previous day, ranging from 3.2 metres to 4 metres, and for many, the official warnings were received too late.

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) had forecast several days in a row that the weather system would move away from Brisbane, and many relied on their experiences of the 2011 flood to plan and make choices. The flood peak was indeed far lower than 2011’s 4.46 metres, but many areas that didn’t flood in 2011 have flooded this year. Flash flooding of creeks was common and the result was that the 2011 benchmark wasn’t entirely useful.

Is the weather getting harder to predict?

As flood and weather forecasters scrambled to update their models in response to heavy, persistent rains, many wondered whether the weather was becoming less predictable. As it turns out, the answer is complicated.

Weather forecasts rely on the laws of physics to understand and model how the state of the atmosphere will change. Observational data collected across the globe are used by weather forecast models to determine the initial state of the atmosphere. The models then solve the physical laws numerically to provide forecasts of temperatures, rainfall, pressure systems, humidity and wind speed.

Professor Julie Arblaster, a climate researcher at Monash University’s School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment and a Deputy Director of the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, explains that in fact, weather forecasting is generally getting better. Thanks to substantially more data observations and increased computing power, weather forecasting has improved dramatically over the past few decades. The BoM’s seven-day forecasts are as accurate as its four-day forecasts were in the 2000s, and 89% of its daily maximum temperature forecasts in 2020-21 were within 2oC of the actual temperature.

Predictions of some extreme weather events have also improved, including the intensification of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 (predicted eight days ahead), the 2010 Russian heatwave and the 2013 US cold spell (1–2 weeks lead time) and tropical sea surface temperature variability following the El Niño/Southern Oscillation phenomenon (3–4 months lead time).

Blame it on the rain

As it turns out, rain is a lot harder to forecast than temperatures, as it tends to be far more localised. To ‘solve’ the weather forecasting equations numerically, the atmosphere is split into grids or cubes as small as 1.5km x 1.5km in city areas but as large as 30km x 30km in some global models. Computational limitations mean that processes like clouds and rain that are very small in scale need to be ‘parameterised’ i.e. simplifications are made to the physical laws to capture and forecast these processes, making the forecasts less reliable.

Despite 50 to 100 years of rainfall records at weather stations across Australia, it’s harder to fill in the gaps between those rain gauges because rainfall is so localised. That makes it harder to assess how good forecasts are, because ‘actual versus expected’ can have quite wide geographic gaps in measurement.

Predictions that are a few kilometres wrong can have significant impacts. Brisbane’s Wivenhoe Dam captures water from only half the city’s catchment area and in the recent floods, much of the rain fell outside Wivenhoe’s catchment, causing flash flooding around Brisbane’s unregulated creeks and making flood peak estimates for the Brisbane River particularly difficult to forecast.

Compound this with the fact that, by definition, there won’t be many instances of extreme events in the historical data, and that makes extreme rain events very difficult to predict.

More research is going into ‘atmospheric rivers’, the relatively long narrow bands of water vapour that transport water from the tropics to other parts of the world and are responsible for about 90% of the water vapour moving from north to south of the planet. Atmospheric rivers were responsible for many of the 2021 floods, and being able to model their movements should significantly improve the forecasting of rain events.

Communication matters

Communication is key says Christine Killip, CEO at Weather Intelligence, a Brisbane-based company providing weather data that helps businesses understand weather-related risks.

“As climate change takes effect, it will be harder for models to rely on historical data, making predictions of extreme events more difficult,” she says. “People need to have the right advice that reflects the potential risk, not just a single rainfall estimate.”

Forecasting centres have moved to ensembles of predictions. The same models are run numerous times with slightly different initial conditions or physics options to see the possible range in outcomes. This is how probabilistic rainfall forecasts are typically developed: ‘a 90% chance of 6-20mm of rain’ is the forecast for my suburb today. Unfortunately, probabilistic forecasts can be hard for the general population to understand, and how we all respond to such information depends very much on one’s understanding of the information as well as one’s risk appetite.

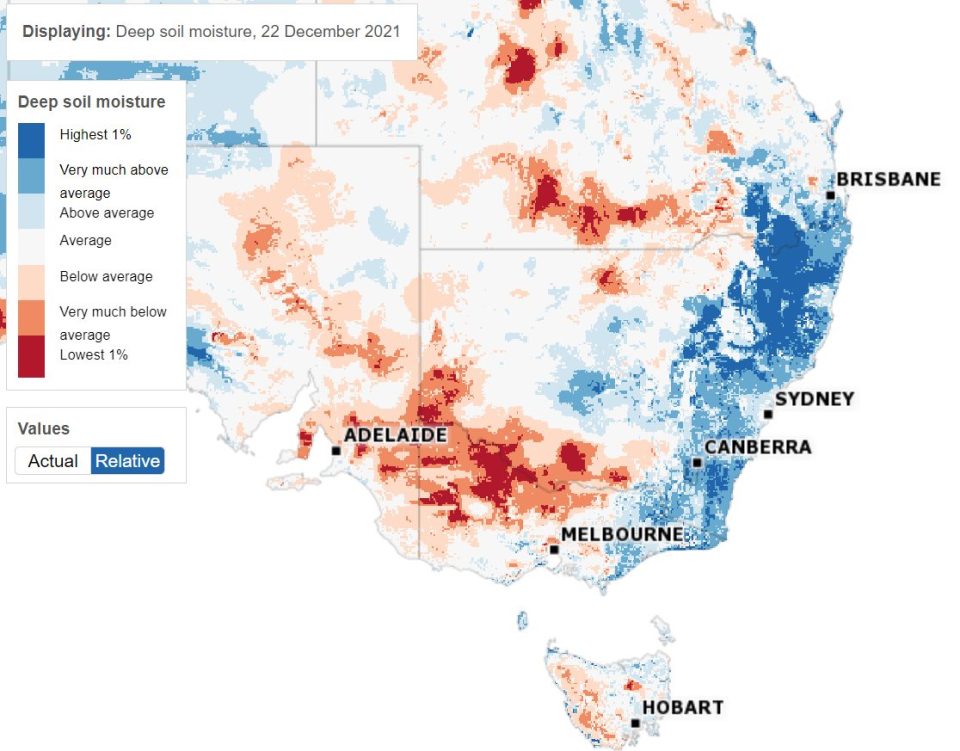

Weather forecasters are already thinking about how to better forecast the impacts of the weather, rather than just the weather itself. Take soil moisture for example. Soil moisture levels affect how quickly water levels rise, how quickly dams fill and which areas flood. Researchers are looking at whether better point data on soil moisture could improve predictions of flooding.

According to the BoM, much of the east coast has been waterlogged since October 2021, with deep soil moisture levels in the highest 1% of measured levels for much of that time. But the risks for property and lives weren’t being discussed and many were caught unaware.

Deep soil moisture levels, south-eastern Australia, 22 December 2021

This contrasts strikingly with our understanding of bushfire danger in Australia. In 2019 the ‘high fuel load’ caused by years of drought was a national talking point and signs on our highways warning of ‘catastrophic fire danger’ meant we all understood the need to prepare.

In contrast, soil moisture and the ongoing La Nina weather system just hasn’t raised the same level of interest, despite the fact its impact could be felt in far more populated areas than most bushfires.

What’s the takeaway for actuaries?

Many column inches have already been written about whether the recent weather events have been a result of climate change, and whether we should be doing more to be resilient in the face of increasing extreme weather events and natural disasters. It’s clear that there are many challenging decisions ahead for Australia as it becomes a ‘harder place to live’.

For actuaries, the past weeks are a timely reminder that predictions are just that – predictions – and they can be wrong. How model results and uncertainty are communicated to others is just as critical as getting the modelling right. Just like weather and flood forecasters, we need to understand how the results of our models will be used by those who read them and ensure that the impacts of uncertainty are transparent and communicated meaningfully.

Equally, if it is extreme events that matter most to users, then that’s where the modelling effort needs to focus.

As for the weather, the BoM expects April to June rainfall to be above average for most of northern and eastern Australia, so it’s worth preparing for a wet Easter and having an evacuation plan if you’re staying in a flood zone.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.