Gender pay gap for Actuaries – Where are we at in 2023?

With flexible working becoming more of a norm nowadays and more affordable childcare put in place, Yulia Lai looks at the actuarial gender pay gap to see if it has improved since Julia Lessing last analysed it in 2017.

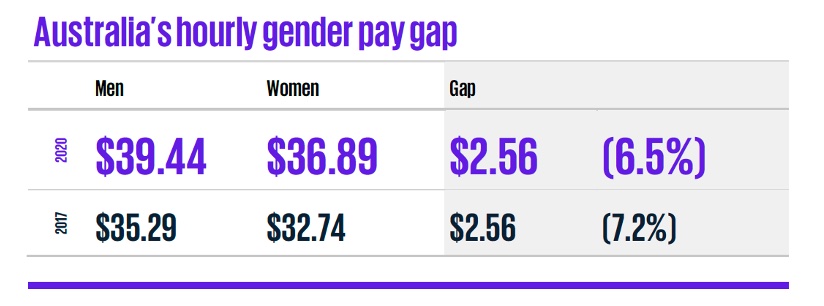

KPMG, the Diversity Council Australia, and the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) have been analysing the gender pay gap in Australia and its contributing factors with the first report published in 2009. The fourth edition of the study released last year, She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap, shows Australia’s hourly gender pay gap has reduced slightly to 6.5% in 2020 (down from 7.2% in 2017)[1].

Source: She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap

In Australia and internationally, the gender pay gap is generally calculated as the difference between the average income of men and women, expressed as a percentage of men’s average income.

ABS data on average full-time average weekly earnings indicates the weekly wage gap has reduced from 20% to 14% over the past 20 years.[2] As of 2022, The WGEA reported the gender pay gap of 22.8% – the same as in 2021.[3] This shows that the gender pay gap still favours men. The differences in the gender pay gap reported in various reports is due to differences in data sources, wage periods (e.g. average hourly wage, average weekly earnings, or average remuneration) and the method used to calculate the gender pay gap.

Do female actuaries earn less than their male counterparts?

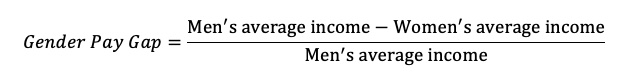

I am curious to find out what gender pay gap exists for actuaries. There is no readily available average hourly earnings for actuaries. So as a proxy, I have used historical and latest average taxable income data from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).[4]

Looking at the average taxable income for the financial year of 2020 (FY20), there appears to be a gender pay gap of 23% for actuaries and 20% for actuarial clerks. These gaps are less than the overall average of 29% across the tax paying population. In the graph below, a slight decreasing trend across the tax paying population is shown over the past few years.

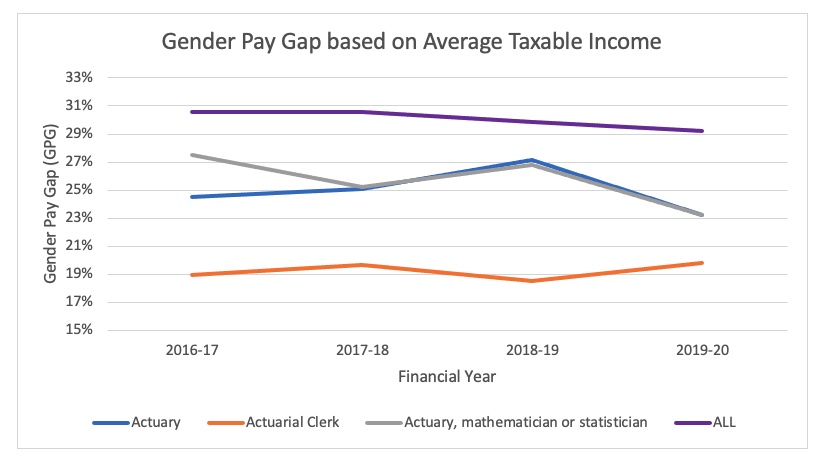

After looking at data by average taxable income, I next looked at data by taxable income ranges. This data is only available at the higher occupation grouping of actuary, mathematician or statistician.[5] This data reveal a noticeable gap in the highest income range, but this looks to be trending downwards. There is no apparent major gender pay gap for the lower income ranges.[6]

Are the statistics correct?

As Julia Lessing noted in the original article – Is there really a gender pay gap for actuaries? – it’s important to compare like-for-like.

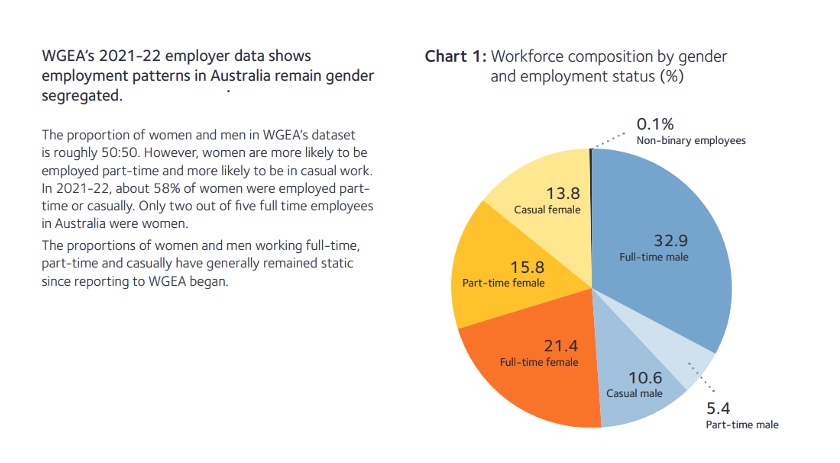

For example, it is important to consider differences in employment patterns between males and females. In FY22, approximately 30% of the workforce consisted of part-time and casual female workers while only 16% of the workforce were part-time and casual male workers[7]. This is shown in the WGEA’s chart on workforce composition by gender and employment status below:

Source: Australia’s Gender Equality Scorecard, December 2022

The data used in the ATO analysis did not consider the type of workforce participation, as this data was not available. As a result, the ATO analysis is inconclusive as to whether there is a gender pay gap for actuaries.

Ideally, we would need longitudinal individual data that tracks individuals across their lifetimes. This would provide data for comparable individuals doing comparable actuarial work. If such data were available for our profession, they would eliminate differences arising from differences in years of experience and labour force participation.

What are the key drivers of the gender pay gap?

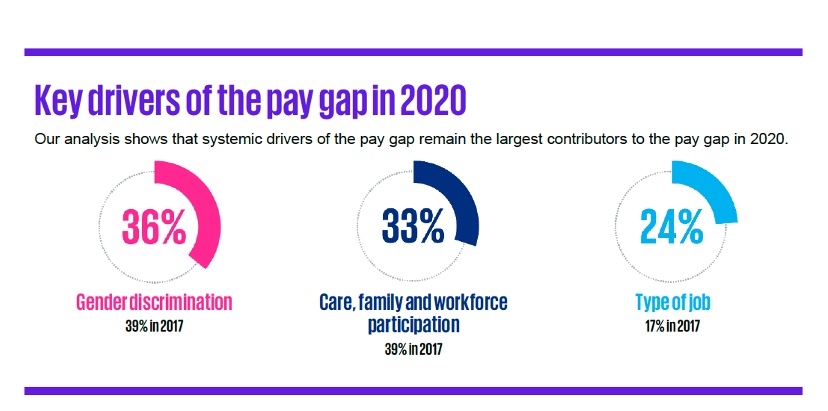

The latest She’s Price(d)less study shows that gender discrimination remains the single most important driver of the pay gap contributing to 36% of the total gap in 2020 (35% in 2017).

The other major contributor is years not working due to interruptions (e.g. parental leave, carers leave) contributing to 33% of the total gap in 2020 (39% in 2017). It is worth highlighting that this is based on all professions and may not necessarily reflect the gender pay gap for actuaries.

Source: She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap

Actuarial researcher, Lesley Traverso, does not see blatant discrimination on salaries when it comes to actuarial roles.

“The actuarial profession demonstrates more equality of gender than many other professions, it is one that everyone is judged equally on their skills and merits.”

The rigorous actuarial qualification process contribute to minimising gender discrimination in our profession.

Lesley Traverso added:

“There are often some inherent disadvantages for women who choose to take a break to have a family or work part-time as was described by survey respondents in my research paper “Identity in Actuarial Careers” (p. 34,35).[8]

“Stepping away from the workforce for even 6-12 months can make a difference in career progression, for example, missing out on a promotion, or not getting a start in new software. So, salary differentials are indicators of the lag in career progression that some women have faced by the family choices they have made rather than by an imbalance on a like-for-like job basis.”

The term ‘motherhood penalty’ springs into mind and I wonder if this would more likely be a significant contributor to the gender pay gap for actuaries?

Women’s earnings are reduced by an average of 55% in the first 5 years of parenthood. This is due to a combination of lower participation rates and reduced working hours.[9] Or perhaps we should say ‘carer penalty’ as it is well-observed that even women without kids tend to take on the caring responsibilities in their family.

What can be done to address the pay gap?

There are many strategies put forward to address the gender pay gap. Employer initiatives, as highlighted by Lesley Traverso, include:

- Enabling parents to juggle more effectively by supporting flexible working.

- Career coaching and mentoring offered to everyone, including parents on paid/unpaid leave.

- Hiring managers ensuring that every shortlist includes a range of diverse candidates.

For the actuarial profession, there are current discussions to ensure that the education and exam structure can facilitate diverse pathways.

Systemic changes across the board include:

- Quality affordable childcare.

- Changes in corporate work hours.

- Changes to school hours.

- Enabling mobility between sectors and occupations.

It is gradually becoming the social norm for fathers to take on more caring roles when children are younger through initiatives such as paid parental leave.

These strategies involve action from everyone – individuals, industry leaders and policymakers.

It is important to maintain research on this topic to stay on top of the issue and continue levelling the playing field going forward.

References

[1] Australian gender pay gap inequality | Economics – KPMG Australia

[2] She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap – Summary report (kpmg.com)

[3] https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/WGEA-Gender-Equality-Scorecard-2022 (agec.org.au)

[4] Taxation Statistics 2019-20 – Individuals – Table 15 – data.gov.au

[5] Taxation Statistics 2019-20 – Individuals – Table 14 – data.gov.au

[6] The lowest income range (less than $18,200) has not been graphed as there was an income loss for females in FY19 which resulted in a 167% gap. No other income losses were seen in the historical data, so this might be an anomaly in the FY19 aggregated data (perhaps one individual had a big income loss unrelated to their salary).

[7] https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/WGEA-Gender-Equality-Scorecard-2022 (agec.org.au)

[8] (PDF) Identity in Actuarial Careers | Lesley Traverso – Academia.edu

[9] Treasury Round Up, October 2022 Children and the gender earnings gap Treasury Round Up 2022 – Children and the gender earnings gap

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.