Careful! Could CDR counterintuitively constrain consumer choice?

In their research paper Insurance Underwriting in an Open Data Era – Opportunities, Challenges and Uncertainties and associated presentation at the 2022 All-Actuaries Summit, Chris Dolman, Kimberlee Weatherall and Zofia Bednarz challenged delegates to think about the implementation and impact of the Consumer Data Right (CDR).

To kick off the presentation, Chris outlined the introduction of CDR in the Australian context, where it has already been introduced to the banking, energy and telecommunications sectors. Open finance (including insurance) has been announced as the next sector.

In essence, CDR establishes the need for ‘data holders’ (organisations within the industries covered by CDR) to maintain designated data sets, from which information may be requested by ‘data recipients’ (accredited firms, within or outside the industry). The impact of CDR includes:

- giving consumers greater control over data held by their bank, or energy company, which could assist them in accessing products or services (such as loans, insurance policies, or energy contracts, or comparison services); and

- protecting an individual’s control and consent as to the use of their data.

This change in how data is accessed could be useful in a variety of ways. For example, current questionnaires used by insurers to acquire information from potential policyholders can be long-winded or difficult to understand. CDR data requests could circumvent these challenges by allowing insurers to access many answers from existing data.

On face value, the guiding principles of CDR favour the rights of consumers. However, applying a practical implementation lens reveals some potential contradictions and challenges which need to be addressed, as is discussed below.

Can you replace existing underwriting questions with CDR requests?

Kimberlee considers this from the perspective of two regulations – CDR and ICA (Insurance Contracts Act).

Does CDR permit this?

The answer is a qualified yes. Insurers can submit a request, as there is no requirement to be part of a declared industry. However, there are some hurdles, including an accreditation process and making technical systems adjustments to allow consumers control over data usage. There are also privacy rules that apply to CDR which extend beyond existing privacy law.

- Data minimisation says that you cannot collect or use more data than is reasonably needed to provide the requested goods or services.

- Stricter rules on consent mean that consumers have to actively consent to secondary uses of data.

Does ICA permit this?

Yes, although this is a little trickier due to the requirement of ICA for consumers to take ‘reasonable care’ not to make a misrepresentation. If a consumer chooses not to use CDR and then makes a mistake in their insurance questionnaire, some may argue that they have not taken reasonable care. This risks an interpretation of the ICA in which using CDR would be compulsory, which is in tension with the consent requirement for CDR.

Ultimately, this potential issue would benefit from further clarification by guidance or reform to ICA and/or CDR.

Can you use CDR to create new underwriting questions?

Zofia analyses whether insurers could use CDR data requests to access information that was previously too complicated to obtain from consumers, effectively creating new underwriting questions.

CDR

New underwriting questions should be permissible if they are justifiable. As above, data minimisation rules require that data is ‘reasonably needed’. This concept does not have a strict and clear definition, and Zofia suggests that guidance will still be needed from industry as to what ‘reasonably needed’ constitutes. This guidance should address industry and societal implications, including fairness concerns (discussed later by Chris).

ICA

The ICA’s 2020 reforms set practical limits on how many and what questions can be asked of consumers. By contrast, CDR data transfer is very easy and could enable insurers to make large, and potentially invasive data requests.

So what happens to underwriting questions? Zofia notes two possible approaches, both of which undermine CDR’s consumer-centric principles.

- Current industry practice is to only provide cover for an applicant who answered all questions. If this is maintained, then adding complex questions may mean that CDR becomes the only option for consumers to provide an answer, reducing their autonomy.

- Alternatively, if insurers make some questions optional and allow consumers to choose whether to answer additional questions with CDR, those who answer more questions will presumably receive some benefits (or else there would be no incentive to provide this data). This, again, may coerce consumers and constrain their choices.

Are the outcomes of CDR desirable?

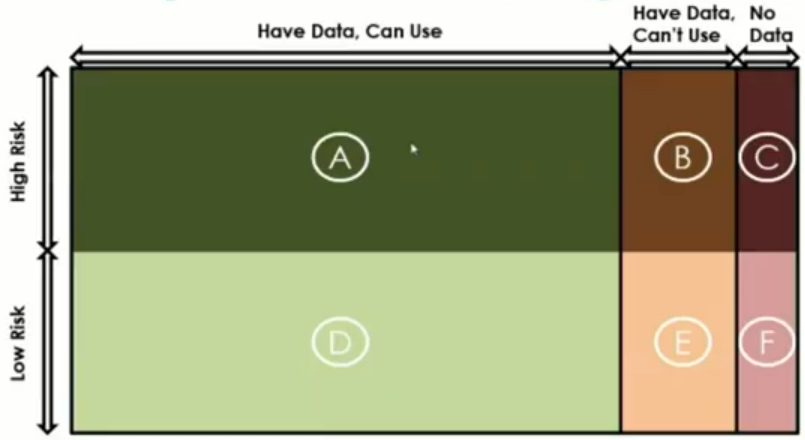

Chris considers a simplified example scenario shown in the table below. We assume that all consumers are either low or high risk, and either have:

- CDR data they are able to use;

- CDR they are unable to use (for example, due to lack of digital skills or access); or

- No data (for example, if they do not have a bank or electricity account).

Consumers in segment D will typically use their data, as they are lower risk and will therefore be able to access a better deal. Consumers in segment A, on the other hand, are likely to refrain, because they are higher risk, and sharing this data may cause their price to increase. All remaining segments are unable to share data. The market now considers two groups – those who share their data (and, from the reasoning above, belong to the lower risk category) and those who don’t (a majority of whom are from the higher risk category). The price for people who don’t share data will therefore increase, regardless of risk status. This may:

- Unfairly punish people who are low risk but don’t have the ability to use data (groups E and F). It is worth noting that the causes of people not having access to data may relate to other forms of disadvantage, including an inability to afford services.

- Force people to ‘pay for privacy’, as those who do not want to share their data will be priced alongside higher risk individuals.

- Create passive consumers. While CDR is based on an assumption of active consumers making active choices, an environment in which CDR becomes the norm may lead consumers to passively accept its use (in the same way that people accept cookies on websites)

All of these outcomes are in tension with the stated aims of CDR, and need to be addressed by consultation with industry, regulators and consumer advocates.

I’d like to thank Chris, Kimberlee and Zofia for a great session, and I look forward to hearing more developments about CDR in future.

| Download a copy of Insurance Underwriting in an Open Data Era – Opportunities, Challenges and Uncertainties. Read further coverage from the 2022 All-Actuaries Summit. |

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.