How the ‘foundation of health’ can shake up insurance underwriting

Researchers investigating the nighttime habits of humans haven’t been sleeping on the job.

Rather the opposite. Recent innovations in sleep science have found that quality, consistent sleep is the foundation of good health and underpins the benefits of regular exercise and a healthy diet.

And with the rise of wearables like Fitbits making sleep data more widely available, will this awaken an untapped resource for the life insurance industry?

At the 2022 All-Actuaries Summit, Nicole Kriek and Matan Abraham considered the impact and implications of sleep patterns as a new rating factor for life insurance products in the concurrent session Sleep, Wearables and the Future of Underwriting.

In their analysis, the two actuaries undertook a series of literature reviews and gathered anonymous sleep tracking data over a ten-month period to underpin their research.

To commence the session, Nicole took delegates through the importance of sleep for maintaining good health.

To provide context, Nicole quoted research from Matthew Walker, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, who has claimed that “sleep is the single most effective thing that we can do to reset our brain and body health each day.”

The Industrial Revolution has bought about negative change to people’s sleeping habits. Nicole explained that while the use of artificial light has generally changed over the past 200 years, its introduction has meant that people now work longer days and work demand has increased.

Nicole shared a 2020 study that found 15% of people in the US sleep less than the recommended seven hours per night. Even worse, 21% of adults get less than six hours and one third don’t find their sleep sufficient.

To emphasise the importance of sleep, Nicole drew a comparison to the human requirement of food, water and air consumption to survive. Humans can live without water for 2-4 days, without food for 1-3 weeks, and without air for around three minutes. But when it comes to sleep, the results aren’t clear. However extreme symptoms occur after 36 hours.

“This includes hallucinations and slurring of speech,” Nicole explained.

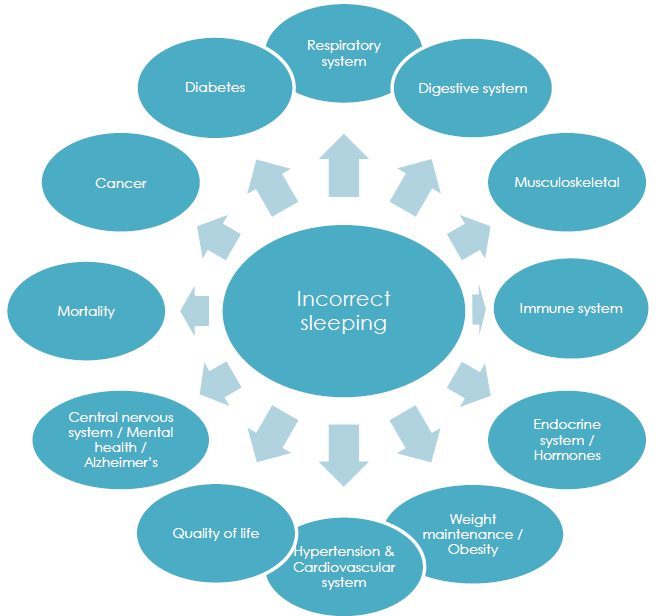

As a starting point for Nicole and Matan’s study, the pair went about gaining an understanding of the impact of poor sleep on the health of an individual and its effect on mortality. As outlined below, the negative effects of poor sleep can be widespread.

Of these factors, the starkest finding was the clear correlation between lack of sleep and mortality. Irregular sleep is linked to poorer health outcomes, across all body systems.

But how can poor sleep among customers impact the life insurance industry?

“Tiredness and daytime sleepiness are increasing each decade, making it a considerable amount of potential policyholders that are experiencing the negative effect of their sleeping patterns,” Nicole said.

“As insurers, through the underwriting process, we may be able to help holistically identify individuals, and provide mechanisms to improve their overall quality of sleep, quality of life, and improved health outcomes.”

To delve into this correlation further, Matan presented their findings on using sleep data in underwriting.

Firstly, the pair explored how sleep data can be used to improve life insurance underwriting and risk management. They set out four goals in doing so:

- Determine how sleep data can be used to identify undiagnosed conditions not assessable by initial underwriting.

- Determine how sleep data can be used to provide early warning signs of the future onset of disease.

- Provide an indication of the severity and effective management of disclosed conditions.

- Identify trends in sleep data over time that can be used to trigger interventions to improve lifestyle wellness.

Matan clarified that polysomnography (PSG), which involves visual and audio monitoring of a patient, is the most effective form of sleep monitoring. But it isn’t for everyone.

“This is not a commercially viable option when it comes to life insurance underwriting. If we have to tell everyone before their underwriting assessment ‘you’re just going to go to hospital, you’re going to sleep there for three nights and then we’re going to attach you to all these machines’, we wouldn’t sell one policy,” Matan said.

So, are there any wearables which provide comparable results to PSG?

Nicole and Matan went about investigating commercial trackers such as Fitbit and Garmin. They provided strongly correlated results to those of PSG for the key metrics they measure.

“What did shine and come through in the data was that Fitbit seems to be the gold standard with regards to trackers in the sleep space, from trackers that are commercially viable at scale,” Matan confirmed.

To enable a user-friendly approach to gathering sleep data within the life insurance context, Matan presented life insurer, Elevate’s customer portal, called ‘ElevateMe’ to the audience. Through a ‘rewards’ program, the portal incentivises policyholders to sync their different dimensions of wellness data (wearables, financials, credit, and clinical healthcare).

“We show it (the various dimensions of a policyholder’s wellness data) in a very exciting dashboard…we not only present this data back to individuals but then we give them goals to achieve on a monthly basis… We motivate them to go on a journey for change, understand their data and their wellness world… and get rewarded for doing so,” Matan said.

“Ultimately this is our mechanism to maintain and manage the risk of our policyholders.”

With their study goals outlined and logistics on gathering effective sleep data figured out, Matan and Nicole then went about gathering key information for their research.

The data was gathered in line with South Africa’s ‘POPIA legislation’ and fully anonymised. Participants used a Fitbit and uploaded data to the ElevateMe portal from 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022.

Matan and Nicole then produced two sample ‘policyholders’ which provided a persona profile of the broader sleep habits of all participants in their study.

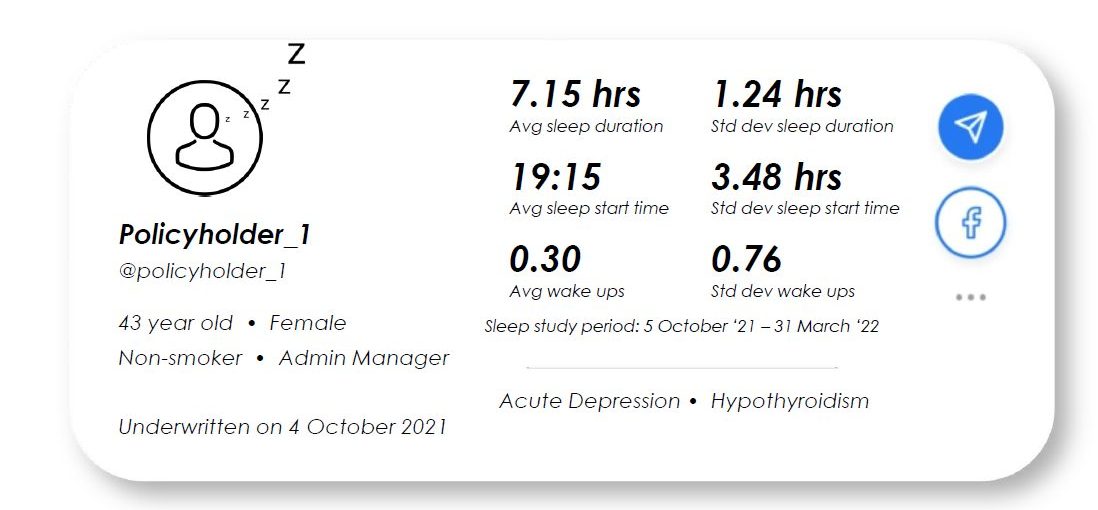

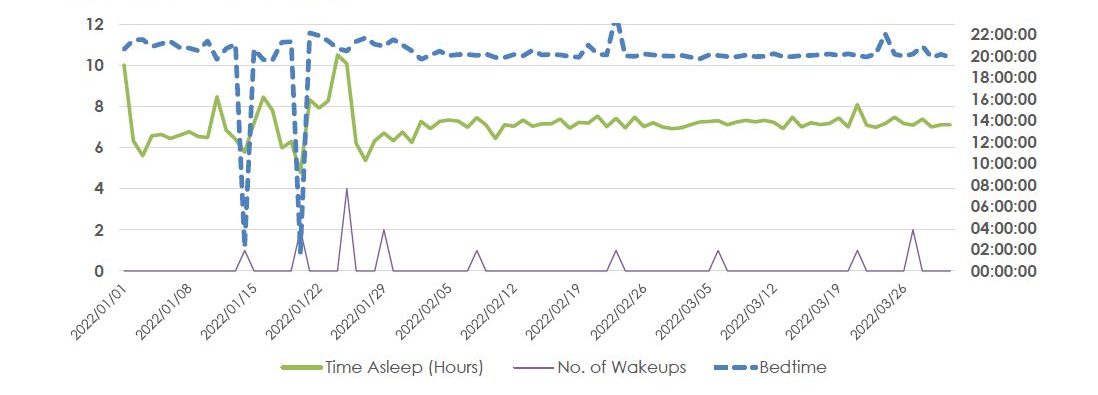

Policyholder #1

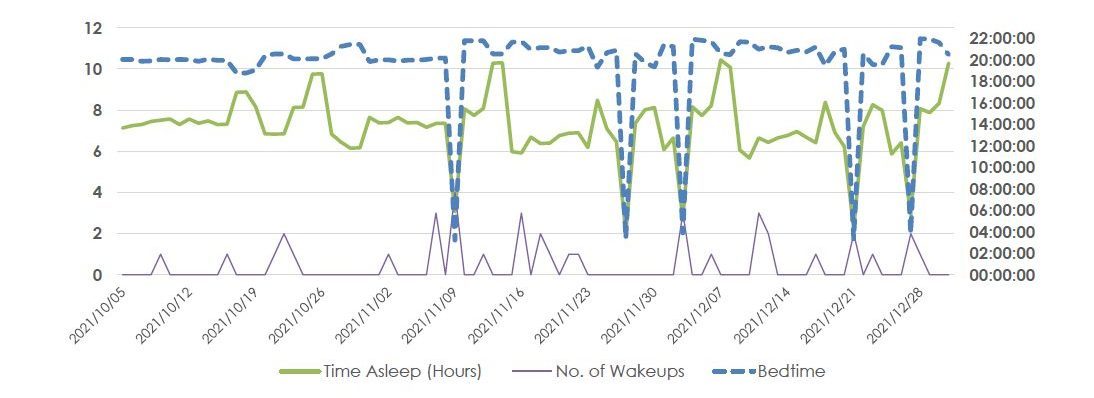

Policyholder #1, whose key figures are outlined in the following image, has acute depression and hypothyroidism. While the average sleep duration of 7.15 hours was “enough”, the standard deviation sleep duration of 1.24 hours, which outlines the range in time within which the participant fell asleep, “it’s a bit of a shocker” according to Matan.

Over the reporting period, Matan and Nicole noted that Policyholder #1’s sleep patterns are very problematic for someone with a mental health disorder and most likely indicate poorly managed mental health.

“Given that we ideally want no more than one wake-up a night, there’s some nights that she’s waking up more than four times, and this is really problematic,” Matan said.

But during the second half of the study period, Policyholder #1’s sleep patterns improved considerably.

Why the improvement? Through analysing Policyholder #1’s insurance claim history, it was determined that her mental health treatment was sporadic in the back-end of 2021. However, in 2022, her treatment became more regular, apparently helping to improve her sleep.

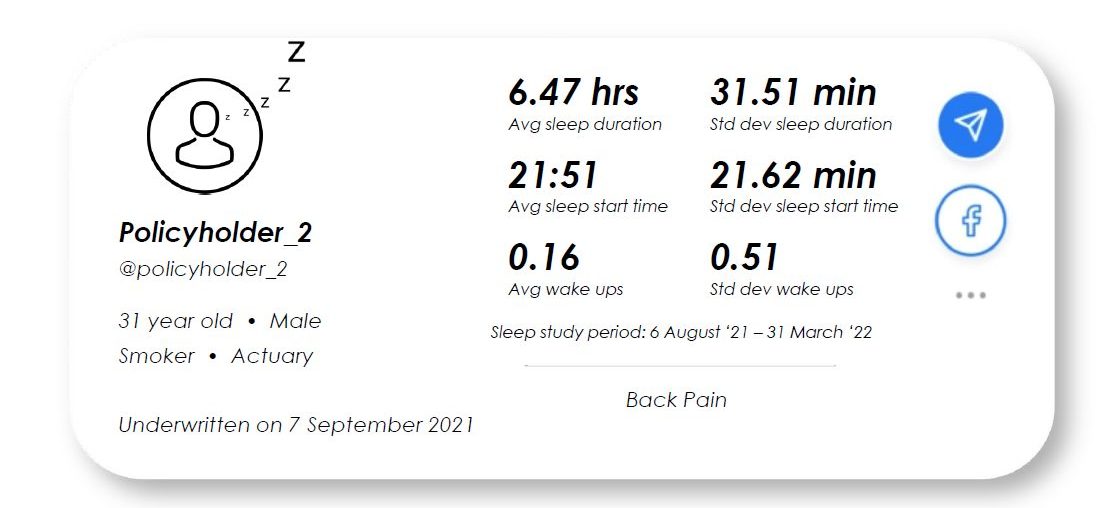

Policyholder #2

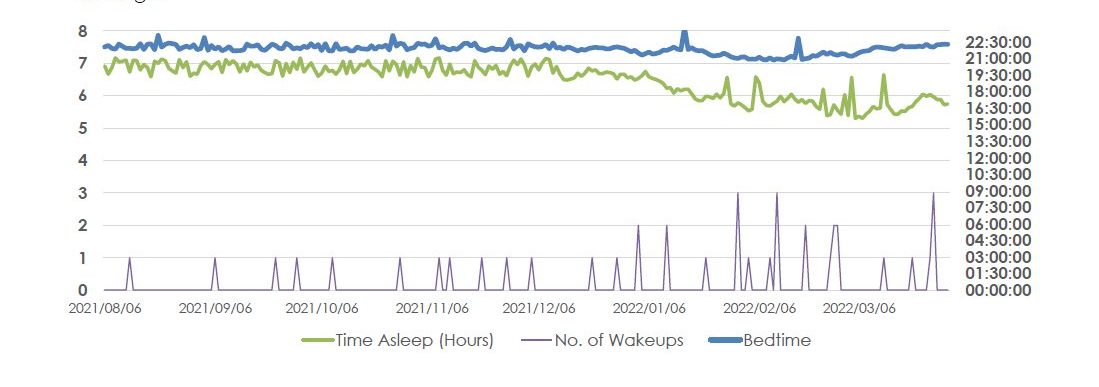

Policyholder #2, who is an actuary with back pain, had differing sleep results compared to Policyholder #1, as outlined below.

Over the course of the study period, Policyholder #2’s quality of sleep declined. By March 2022, he was sleeping markedly less, more sporadically, and getting to bed later.

In this case, it was likely financial stress that was causing the change in sleep patterns.

“This individual in 2021, from a financial perspective, was doing great. But his credit score dropped off a cliff into 2022: missed payments, looking for more credit from the bank,” Matan said.

“This showed that the underlying cause for this individual, by looking at his situation holistically, was that financial difficulty was completely changing this person’s life.”

Where to from here?

Matan outlined the steps required to integrate sleep data into the broader underwriting process. These include further exploration of the data analysis, defining the underwriting protocols for the use of new data, and monitoring and enhancing the protocols and models in place to determine areas of refinement.

“This is a broader exercise that we’re looking at quite holistically from an individual to see how data can be used to support a new wave of underwriting that is a lot more personal, a lot more needs-focused, a lot more personalised with regards to understanding the individual, both at the time of onboarding and then ongoing through the life of the policy to be able to assess the risk that much better,” Matan said.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.