COVID reflections – the Long COVID special

What do we know about the risks of Long COVID? It can be very serious, enough that avoiding infection is a good idea. But how likely is it? It’s very hard to measure. This article takes a closer look at Long COVID, what we know about how risky it is, and how serious it is.

‘Long COVID’ is increasingly recognised as a long-term complication of contracting COVID-19. But what is it? And how worried should we be? Since I last dived into the research a year ago, there are studies everywhere. But it still isn’t clear how risky, and how bad it really is. From a deep dive over the past few weeks, Long COVID seems to be a combination of things, most notably long term damage to many different organs in the body as a result of COVID-19, and long term post-viral complications, similar to those that occur in many other viruses (here in Australia often clustered into Chronic Fatigue Syndrome). That makes it very hard to study, and quantify, particularly as many of the symptoms are hard to pinpoint and very variable.

In general, what we do seem to know is:

- There is a non-trivial chance of being seriously disabled for a prolonged period by Long COVID for those who contract COVID-19.

- The chances of Long COVID are higher if the initial COVID-19 illness was worse.

- Long COVID affects people of working age more than children and older people.

- Women seem to be affected worse than men.

- Vaccination reduces the chances of long COVID.

- A wide variety of organs can be affected long-term by an initial illness of COVID-19.

- Long COVID outcomes have a wide range, from ongoing mild symptoms to serious limitations on day-to-day activity.

There are implications from the long-term severity of this COVID-19. At a societal level, we should continue taking steps to avoid widespread infection. These are not just about avoiding acute illness, pressure on a hospital system and deaths, but also about reducing long-term levels of disability. And we need to be ready to support those people who do come down with long COVID – both financially, and with improvements to the capacity of our health system. And I hope we continue to expect and support people who are unwell isolating themselves to avoid infecting others, both at a government level, and an employer and individual level.

What is Long COVID?

This article from Dr. Achim Regenauer is a great summary of what we know so far. His overall description:

|

The list of long COVID symptoms is now longer (at over 200), there is still no one clinical case definition (although the WHO’s ICD-10 U09 is a helpful reference2), no clear routine laboratory or imaging diagnostics, no clear duration, and no effective treatment (nor is one in sight)….it has unknown but potentially long-term duration, lack of a uniform, internationally applied definition, and complex, diverse set of symptoms, including post-viral fatigue, joint pain and organ-centered manifestations, such as impaired lung function.

|

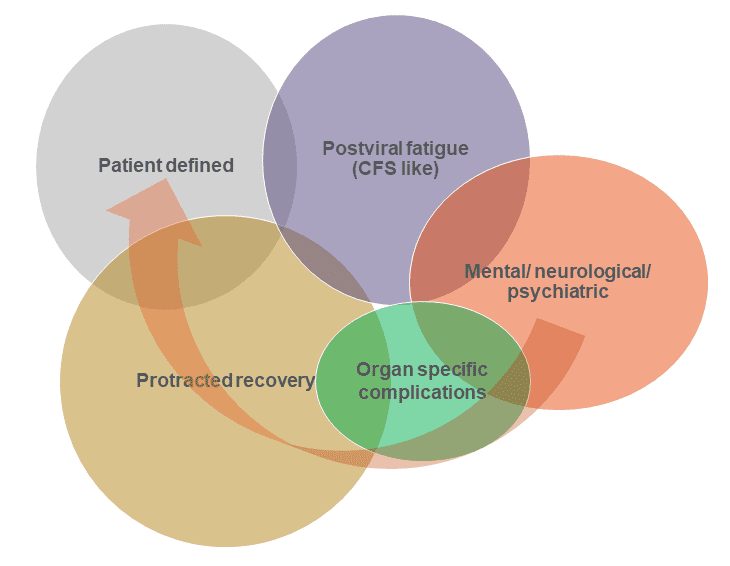

It is likely that Long COVID has multiple COVID-related causes, as shown in the figure below (in which Dr. Regenauer has tried to demonstrate the likely proportions of the different types of COVID-caused long-term diseases). They are likely to have overlapping systems, but potential separate causes:

- Postviral fatigue – a well-known phenomenon from many viral diseases, including the 1918 flu pandemic, and polio, as this article describes.

- Organ-specific complications – there are documented examples of damage to specific organs post COVID infections – e.g. this study of cardiovascular outcomes shows heart damage is much more likely post a COVID infection than in patients with other respiratory diseases, and this study looks at damage to the heart lungs and kidneys.

- Mental/neurological/psychiatric – this study looked at long-term nervous system consequences of COVID-19 and found a number of different neurological and psychiatric outcomes (this may be a subset of organ-specific complications, but for the brain).

- Protracted recovery – COVID-19 is a complex disease, and it seems likely that some patients take a long time to recover.

- Patient defined – covering symptoms with as yet unknown causes that aren’t caught above.

|

How likely is Long COVID?

Now that we are two years into this pandemic, it is possible to look at long-term diseases. But the nature of the surges around the world, the disruptions to the health system for those who are not acutely ill, and the vagueness of many symptoms have made Long COVID particularly challenging to study. Given Long COVID is probably a combination of a number of different underlying causes, which have different trajectories (e.g. protracted recovery will get better over time, but the organ-specific complications may well get worse), and a complex constellation of symptoms, it is very hard to measure the overall risk. The lack of testing early in the pandemic, (so considerable unidentified illness) also makes measurement difficult.

The gold standard would be a prospective study that recruits a random selection of people testing positive for COVID-19, matches them with similar people (from an otherwise identical population) who test negative for COVID-19 and then tracks them both for an extended period. But the complexity of the wide variety of symptoms makes even this difficult,

But even then after that extended period, it is more challenging than it appears to define Long COVID, given how variable the symptoms are in a way in which statistical comparisons can be usefully made.

|

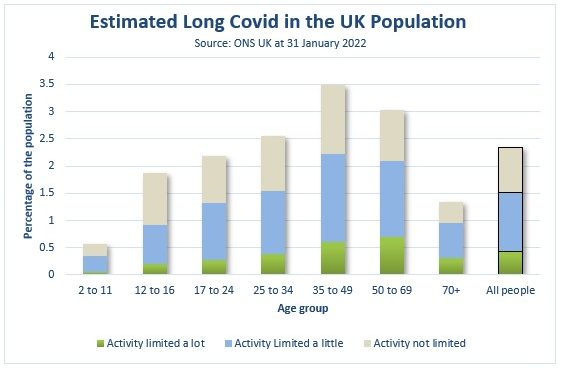

The UK Office of National Statistics (ONS) does a population-level survey asking respondents about their symptoms of Long COVID. They release statistics regularly. Their latest survey (as of 31 January 2022) samples the whole population, given the challenges of identifying those who have definitely had COVID-19). Overall, 2.4% of the population was estimated to have some symptoms of Long COVID at least four weeks after their COVID-19 illness (based on the self-reporting of both the initial illness and the subsequent symptoms of the sample) and 0.4% of the population had their activity limited a lot by their symptoms.

In the UK, the total reported cases to the middle of December (the midpoint of four weeks before this survey was conducted) were 16% of the total UK population (from Our World in Data). So, if those were all the cases, 2.7% of all verified COVID-19 cases have led to serious activity limiting symptoms, with up to another 6.8% of verified COVID cases leading to some limits on activity. Both the numerator and the denominator of this measure are likely to be inaccurate; there were almost certainly more cases than this, but also some people would not have identified themselves as having Long COVID because they won’t have realised they had contracted COVID.

This study suggests that at least 0.4% of COVID Cases caused Long COVID with serious life-limited symptoms for a prolonged period – which was the proportion of the total population of the UK reporting this outcome in the latest study. This outcome is more likely in those of peak working age – 35-69.

How much does vaccination help?

Many of the studies of Long COVID in this post occurred before the population was generally vaccinated. So there is limited information about the likelihood of Long COVID post-vaccination, but what there is suggests a reduction in risk by around 40-50%. This study is the most comprehensive of the ones in this thread.

This seems intuitively plausible, given that the risk of Long COVID reduces with milder disease, as well as some evidence that vaccination helps reduce symptoms for those who already have Long COVID, it seems likely that vaccination reduces your risk of Long COVID, but it doesn’t eliminate it (just as it reduces but doesn’t eliminate the risk of hospitalization and death).

Some individual diseases that have increased prevalence post-COVID?

It is very difficult to look at specifics with Long COVID as there are so many different types. So, this final section looks at some major studies of long-term outcomes of specific diseases or serious hospitalisation post-COVID (which is one aspect of Long COVID).

First, a very recent study into overall hospitalisation and death post-COVID-19 in the UK, a very recent preprint study based on the UK biobank (around 400,000 total people). It looks at the risk of subsequent hospitalisation from a wide variety of diseases and disorders – all of which have increased substantially, noting that COVID-19 disease of any kind is associated with an increased risk of subsequent mortality and hospitalisation, with the risk increasing the more severe the disease – a 24% increase in mortality risk subsequent to mild COVID-19, and mortality nearly 15 times higher for those with severe (hospitalised) COVID-19.

|

Overall, we found that COVID-19, especially severe disease, was associated with increased risks of hospitalisation and/or mortality due to pulmonary, cardiovascular, digestive, neurological, genitourinary and musculoskeletal disorders in the post-infection period. These results were largely consistent and robust to multiple sensitivity analysis, and after PERR and PTDM adjustment.

|

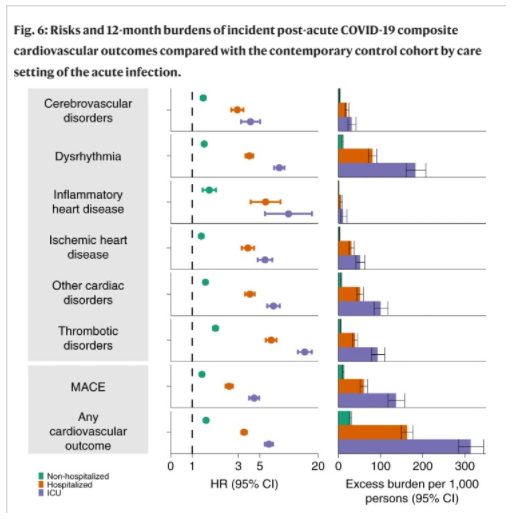

Turning to individual diseases – Cardiovascular disease. This study from the US looks at the long-term cardiovascular outcomes post a COVID-19 infection. It uses data from the Department of Veterans Affairs to match COVID-19 infected individuals with control individuals (selected to match the characteristics of those with a COVID-19 infection). And then it investigates various cardiovascular diseases more than 30 days after the initial infection date (or start date for matched non-COVID individuals, who were matched according to the severity of initial disease).

The diagram below shows that the risk of a major adverse cardiac event (MACE) is substantially higher post a COVID-19 infection than in the controls, with a hazard ratio of 1.55 (the chance of MACE after COVID-19 is 155% that of the control). That poor outcome is considerably higher if the initial COVID-19 infection led to hospitalisation, or intensive care, with major adverse cardiac events more than five times more likely in post-COVID-19 ICU patients than the control patients, with a disease burden of over 15% – i.e., an extra 15% compared with controls of Post-COVID ICU patients had a major adverse cardiac event in the 12 months after their COVID-19 diagnosis.

|

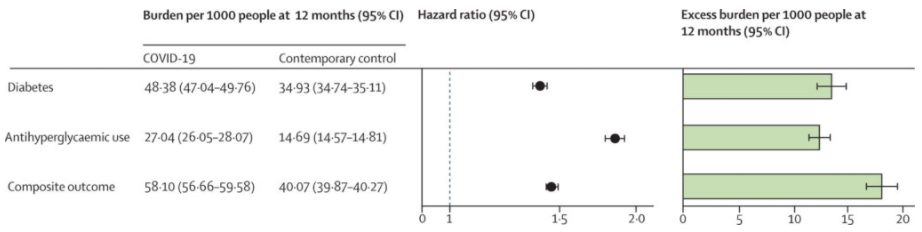

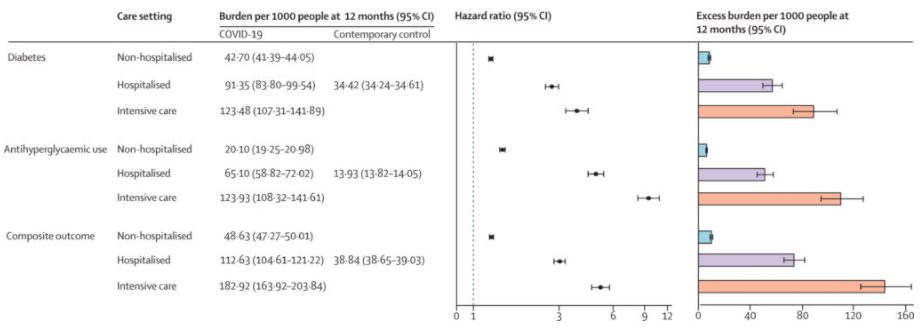

Next, Diabetes. This study also uses data from the US Department of Veterans affairs. The problem with this is that it is disproportionately a study into men (nearly 90% of those studied), but it is a very large group of people – in this case around 150,000 COVID positive cases compared with around 3 million controls.

|

The table above shows that COVID-19 increases the risk of diabetes by around 50%, and overall increases the proportion of the population with diabetes by just over 1%. And as has been common in almost all the studies I have looked at, the worse the initial COVID-19 disease, the bigger the increase in the follow on disease as you can see from the table below. The conclusion of the paper is quite clear.

In conclusion, we suggest that in the post-acute phase of the disease, people with COVID-19 exhibit increased risk and burden of diabetes, and antihyperglycaemic use. The risks and burdens were evident among those who were non-hospitalised during the acute phase of the infection and increased according to the severity of the acute infection as proxied by the care setting (non-hospitalised, hospitalised, and admitted to intensive care).

|

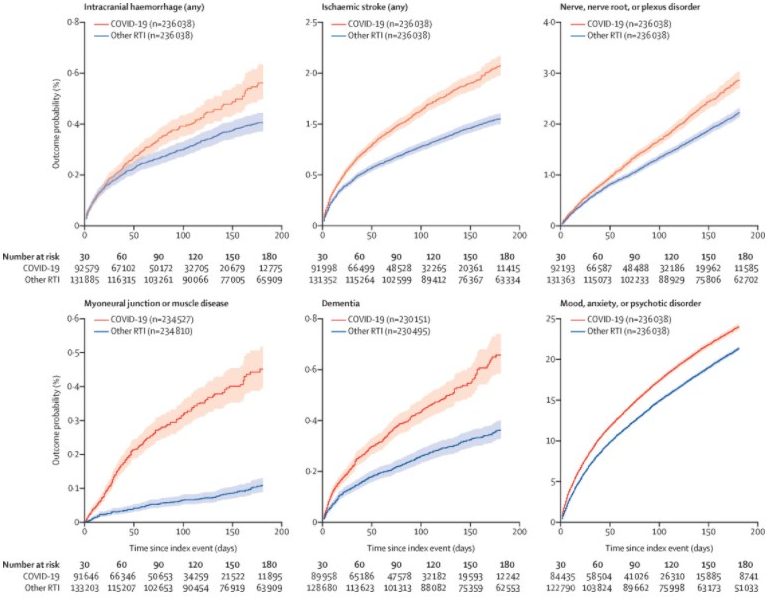

And finally, a study from nearly a year ago from the US looks at the impact of COVID-19 on brain health in the six months following a COVID-19 diagnosis. They used health care records from a number of different health care organisations, comparing those diagnosed with COVID-19 with those diagnosed with flu or another respiratory disease.

|

Most diagnostic categories were more common in patients who had COVID-19 than in those who had influenza (hazard ratio [HR] 1·44, 95% CI 1·40–1·47). As with incidences, HRs were higher in patients who had more severe COVID-19 (eg, those admitted to ICU compared with those who were not: 1·58, 1·50–1·67, for any diagnosis).

Our study provides evidence for substantial neurological and psychiatric morbidity in the 6 months after COVID-19 infection. Risks were greatest in, but not limited to, patients who had severe COVID-19. This information could help in service planning and identification of research priorities. Complementary study designs, including prospective cohorts, are needed to corroborate and explain these findings.

In general, what we do seem to know is:

- The chances of Long COVID are higher if the initial COVID-19 illness was worse – all the organ studies show this.

- Long COVID affects people of working age more than children and older people – as suggested by the UK study.

- Women seem to be affected worse than men – most studies show this outcome.

- Vaccination reduces the chances of long COVID – a wide variety of study outcomes, but settling on 50%.

- A wide variety of organs can be affected long term by an initial illness of COVID-19 – any study on an individual organ seems to show some effects.

- Long COVID outcomes have a wide range, from ongoing mild symptoms, to serious limitations on day to day activity – there are over 200 symptoms identified

- Overall, there is a non-trivial chance of being seriously disabled for a prolonged period by Long COVID for those who contract COVID-19 – at a population level, at least 0.4% of the UK population have identified this outcome, the proportion of COVID cases with a medium-term serious disability is likely to be higher than this.

|

This article was originally published on Actuarial Eye by Jennifer Lang. Read it here.

|

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.