PHI funding model change to address affordability

Tony Ly, Actuarial Manager at Bupa, proposes a new funding mechanism for private health insurance to address the current affordability crisis.

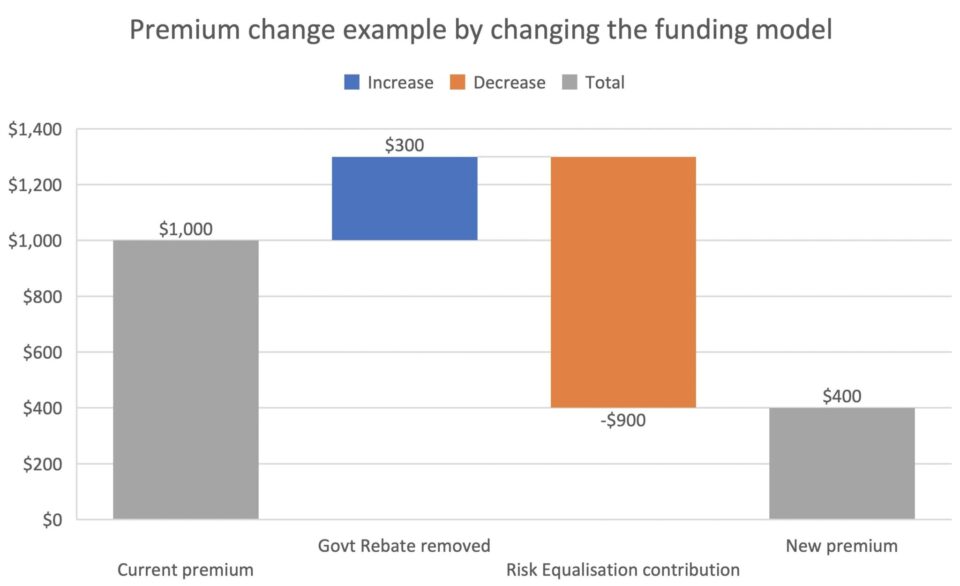

The cheapest private health insurance hospital product I could find in Victoria was around $1,300. Allowing for the government rebate of around 25%, the price of this policy is around $1,000. One would wonder why it is so expensive, given:

- it’s the cheapest hospital product available comparing all health funds; and

- it has minimal coverage.

What if the following could be implemented for this policy along with all the other hospital policies in the health insurance industry in Victoria by changing the funding model for private health insurance?

The consumer will no longer receive the government rebate so the price to the consumer increases by $300 to $1300. However, there is a premium reduction of $900 to bring the final price to $400. So how could such a large reduction in price be possible for all hospital policies in Victoria? To consider this, we first need to understand the cross subsidy in risk equalisation.

Problem

A major factor for the high prices in private health insurance is the risk equalisation contribution which is paid by every private health insurance policyholder. The (more) technical term for the risk equalisation contribution is the ‘calculated deficit per single equivalent unit’ in the health insurance system. Essentially, this is the cross-subsidy payment that all adult customers with health insurance need to pay to balance the higher costs generated by older demographic hospital costs. For example, in the graph pictured above, $900 of the $1,300 total premium received by the private health insurer will be redirected to pay for the hospital costs of older members.

The current state of PHI funding system

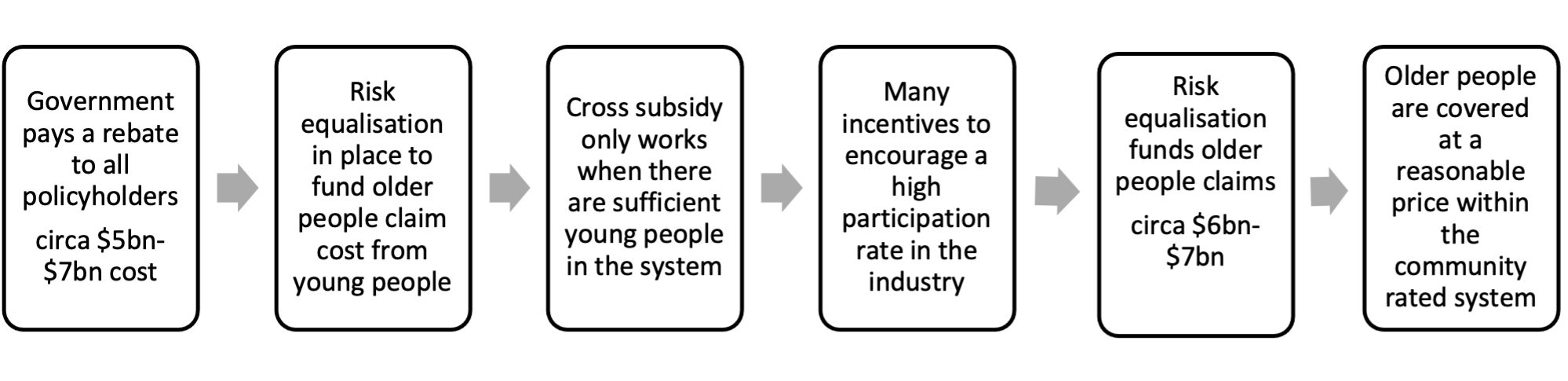

One of the objectives of the current system is to enable community rating and ensure the older age demographic are able to purchase PHI for a reasonable price. As described above, this is currently achieved by charging all policyholders the risk equalisation contribution, which embeds a cross-subsidy into the system. However, this is currently achieved through a convoluted process.

The current system is summarised in the figure below:

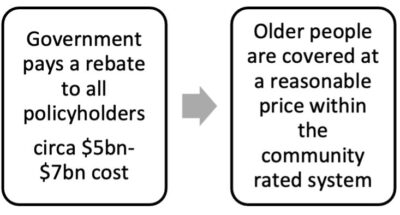

Possible future state of PHI funding system

The current system takes a detour to the desired end state. A possible future state skips through this complicated detour altogether. Applying the rebate directly to the older age cohort removes the need for risk equalisation. This future state is summarised in the figure below:

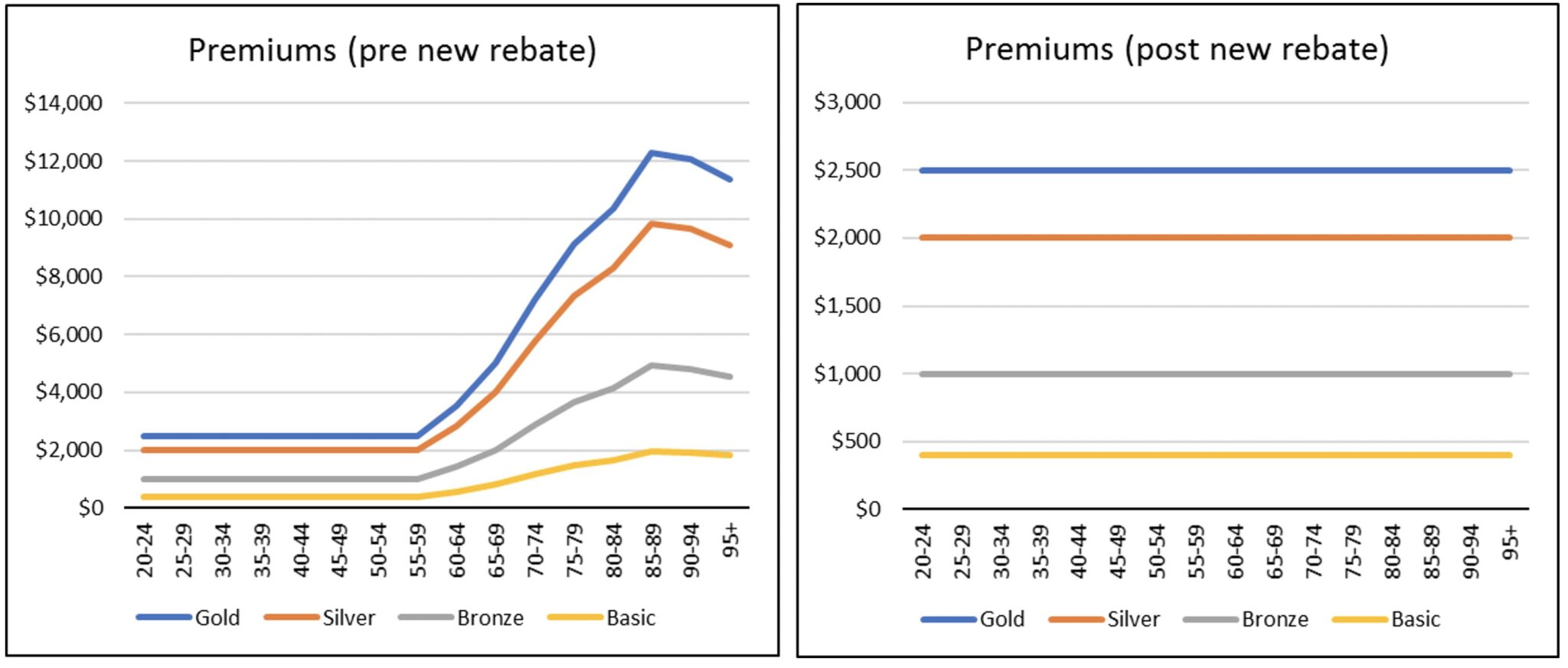

The following two graphs show an example of how this future state could be applied to the hospital products currently in the health insurance system.

The graph on the left is the amount the insurer would charge pre-rebate for coverage and reflects the claims cost risk profile by age. The new rebate amount by age would be in a similar pattern to the current Age Based Pool amounts. The graph on the right is the premium amount post-rebate that consumers would be charged which is uniform across all age bands, i.e. community rated. The rebate amount by age would be an industry-wide percentage calibrated in a similar fashion to the current age-based pool percentages.

The current state has a high average premium cost for young people as a large proportion of their premium is to fund the risk equalisation contribution. By removing the risk equalisation contribution, the average price for young people substantially decreases. By reducing this price barrier for young people, it will arguably incentivise more young people to take up private health insurance.

This proposal effectively redirects the government rebate into risk equalisation. The two balances have been moving in opposite directions with the government rebate decreasing due to the annual indexation and risk equalisation increasing due to the increased costs and utilisation of health insurance claims. That means this proposal will require a higher contribution from the government in the long term.

Objectives met?

Change is always difficult, especially when systems and rules have been ingrained in an industry for many years.

One potential objective in introducing change is to have minimal disruptions to the industry. The benefit of this proposal is that it will keep all of the existing and recent reform items. The proposal retains community-rated premiums, which means all the ‘carrots and sticks’ in the system remain unchanged. This means the MLS (Medicare Levy Surcharge), LHC (Lifetime Health Cover), ABD (Age-Based Discount) and GSBB categorisation can all remain as they currently exist.

Furthermore, with possible hospital premiums around $400, assumedly, there would be an increase in the participation rate, especially if the Medicare Levy Surcharge (MLS) thresholds are kept the same. This higher participation would benefit the private health system and also help alleviate pressure off the public hospital system.

Another benefit is that excess levels in the industry can reflect the true underlying risk/cost. With the risk equalisation contribution removed, the industry can have hospital cover that reflects underlying claims experience. i.e. $3,000 excess level products could exist with the appropriate price to reflect that excess level.

Concluding remarks

In summary, there is no single silver bullet to fix affordability in the health insurance industry. This article addresses a new possible funding mechanism use of the rebate. To manage the long term rising health costs, there will need to be fundamental changes to how private healthcare operates in conjunction with the public system. This proposal showcases how the government rebate could be invested as opposed to the complex detour system that is currently in play.

This article is a personal opinion piece drafted independently and the views presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of any organisation, including BUPA or The Actuaries Institute.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.