Why COVID-19 fatality rates look so different across the globe

As the pandemic continues to develop around the world, our knowledge of the disease will improve, as will the quality of data. Kirsten Armstrong takes a look at the reasons behind varying global fatality rates.

|

Definitions In this paper I’ve used terms preferred by epidemiologists when they talk about mortality rates from disease. Epidemiologists use the terms infection fatality rate (actual fatalities from a disease divided by the true number of people infected with the disease) and case fatality rate (reported fatalities divided by reported cases, ie those who test positive). The infection fatality rate is of most interest, but can only be estimated through population studies or making inferences from the case fatality rate and estimated reporting rates. |

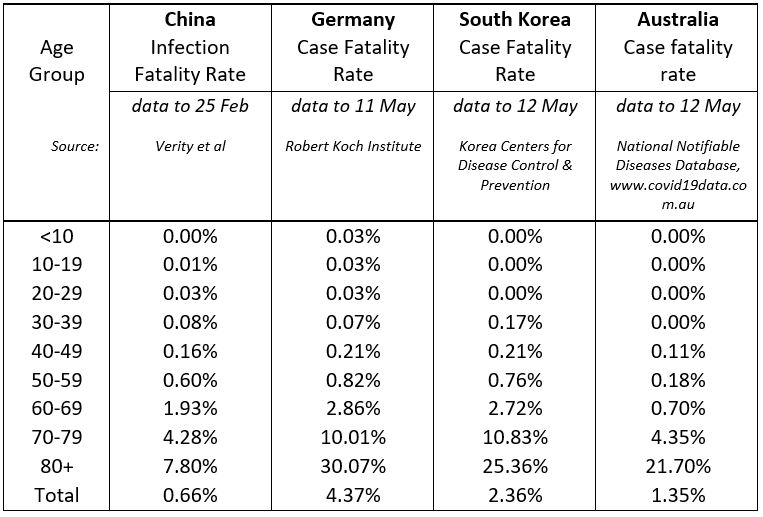

Estimates of the fatality rate for COVID-19 are varying widely across countries, over time and as we learn more about the disease. My own best estimate of the case fatality rate (see definition above) we should expect in Australia is about 1.5%. That’s based on a detailed study of experience in China that estimated infection fatality rates by age group, and adjusting for the estimated reporting rate in Australia. It also takes into account the higher case fatality rates we’ve seen for the over 80s in countries like Germany and South Korea that, like Australia, have relatively more people aged over 80 and 90 than China, but have managed testing and health services well throughout the pandemic. Reported fatalities in Australia are tracking relatively in line with this estimate so far.

Table 1: Infection and Case Fatality Rates, selected countries.

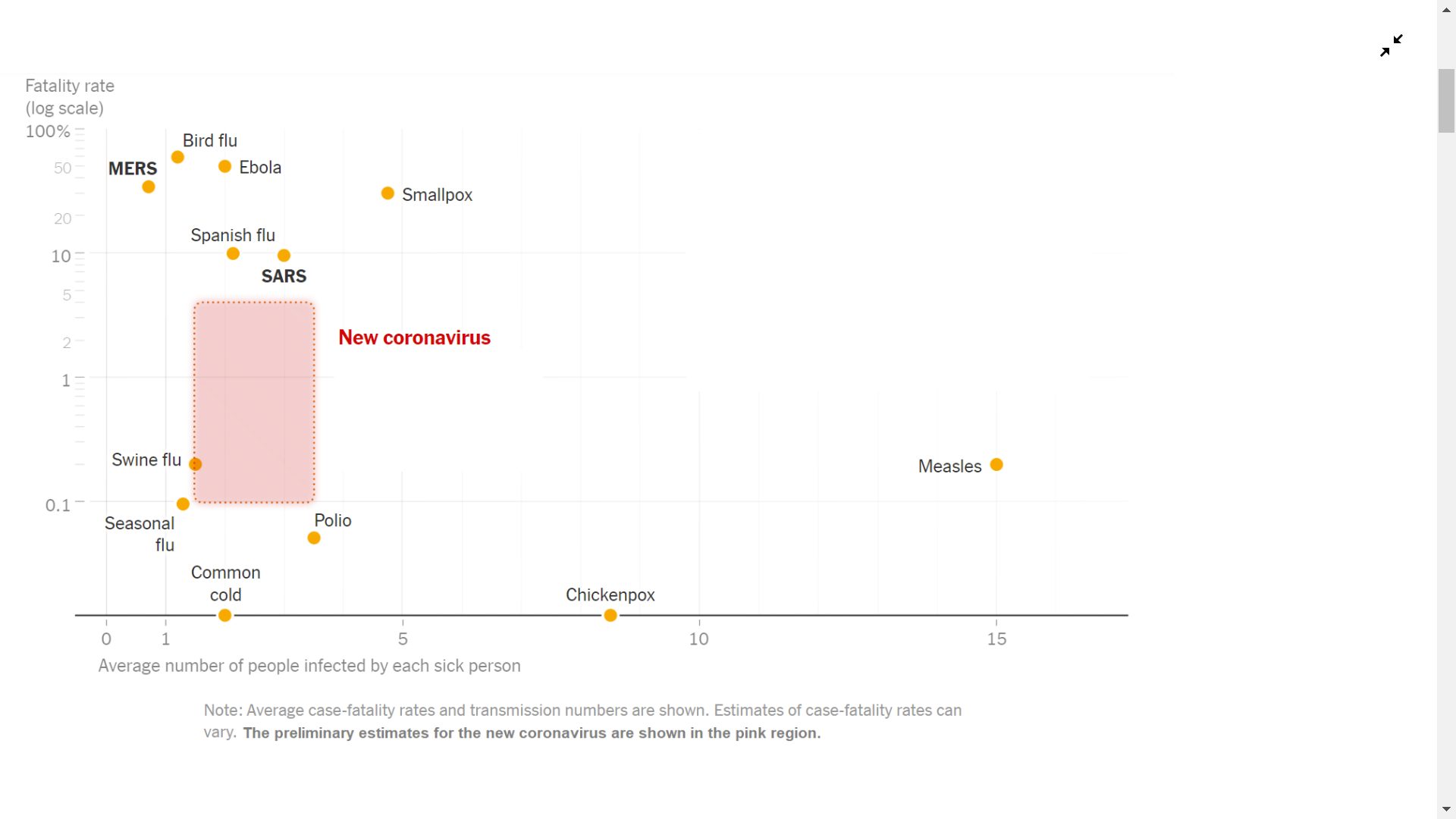

That makes COVID-19 significantly more deadly than the common cold or seasonal flu, but far less deadly than other recent epidemics like SARS, MERS and the Bird flu.

Figure 1: Case fatality rates and rates of infection from diseases in history.

Source: New York Times.

But why are the fatality rates we’re seeing across the globe so different? Data quality and different measurement approaches both play a part, but there are some very real differences across countries that will lead to vastly different fatality rates.

Data and measurement

Differences in the way data is reported across countries mean that comparisons are difficult. That means a need to delve into any data to make sure it’s valid and usable for any purpose you need.

Cases versus Infections. One trap is whether a study reports the case fatality rate or the infection fatality rate. Most of the data we see uses data on the number of reported cases and reported deaths, so is a case fatality rate. But with anywhere between 5% and 80% of infections being asymptomatic, it’s possible that many people who are infected simply won’t get tested, so the gap between the true number of infections and the reported number of deaths and cases could be very wide.

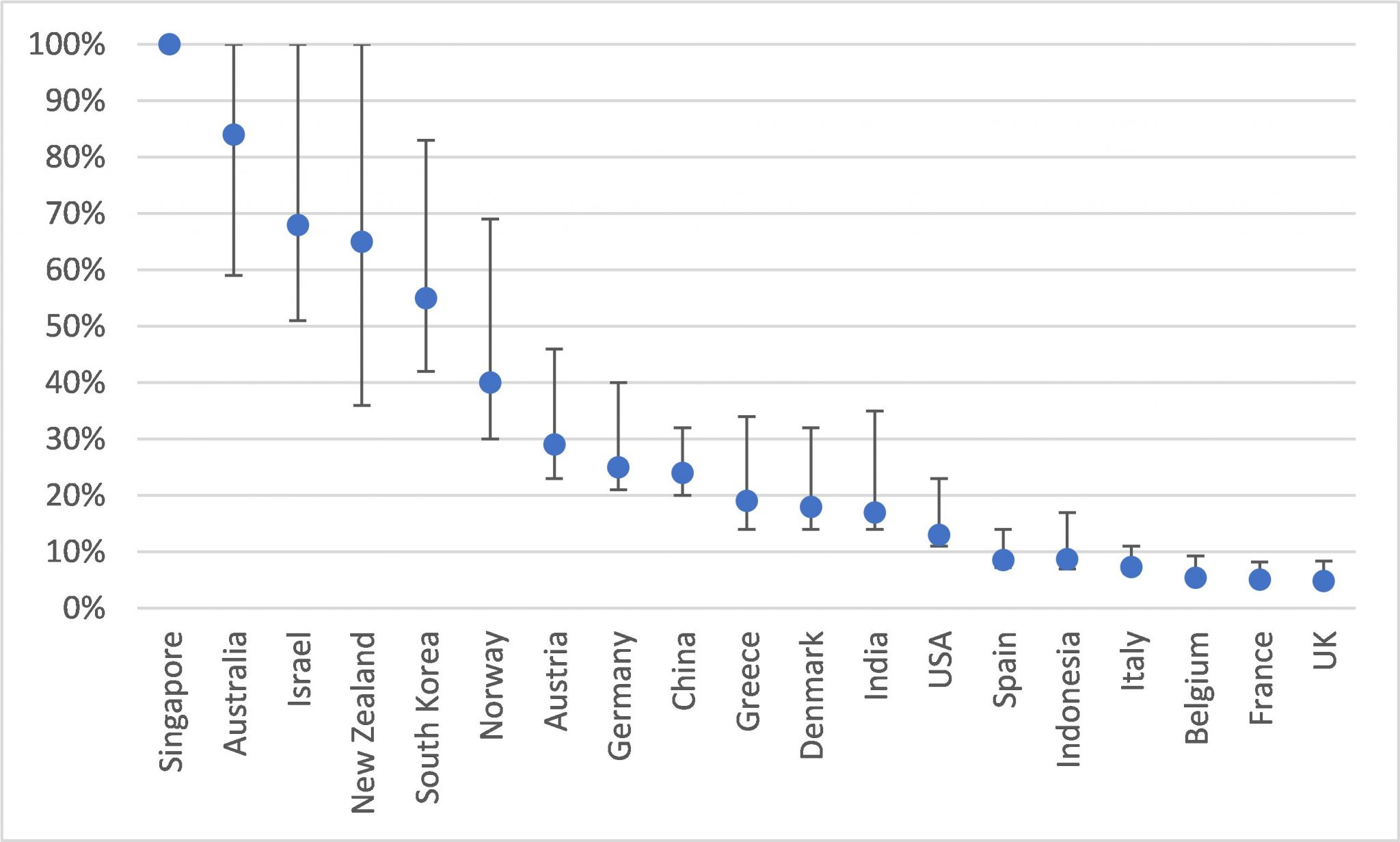

Different testing regimes. By far the biggest difference in case fatality rates across countries is how rigorous testing regimes are, and what proportion of infections are being identified and reported as cases. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has developed a methodology that works back from numbers of deaths and testing rates to estimate what proportion of cases are likely being reported. We are seeing very high case fatality rates in countries like the UK, Italy and France, where testing rates have been relatively low, whereas countries like Australia and South Korea that have maintained high levels of testing throughout the pandemic have reported far lower case fatality rates. That should give more confidence in the case fatality rates coming from these countries.

Figure 2: Estimated percentage of symptomatic cases reported (95% confidence interval), selected countries, 30 April 2020

Source: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Different definitions and measurement of deaths. On 12 February, China changed the definition it used for COVID-19 cases and deaths – the result was a spike in both, that the world noticed. In fact it was not the first, nor the last time that the definition was improved, as more was learnt about the disease and testing improved. One study estimated the impact of successive new definitions might mean that the true number of cases in China through to 20 February might actually be four times higher than first thought.

The WHO has released a standard definition, but it’s clear that reporting remains inconsistent. The UK was initially counting only deaths occurring in hospitals, so experienced a spike when deaths in nursing homes were added to the count. In other countries, health systems have struggled to test all people who died and have made different choices about how to report fatalities as a result. Italy reported deaths based on patients who had tested positive to COVID-19, but statistics released last week revealed that deaths in Italy were 49% higher in March this year compared to prior years, but only half of that is accounted for by known COVID-19 deaths. It’s likely that many of the remaining excess deaths are unreported COVID-19 cases.

At the other end of the spectrum, Belgium has surged to the top of the leaderboard in terms of deaths per capita, but the numbers may be an overestimate. The mere suspicion of COVID-19 is enough for nursing home deaths to be included in the statistics – last week just 4.5% of nursing home deaths had been tested to confirm COVID-19 was present.

Time delay. With deaths from COVID-19 occurring anywhere up to eight weeks from infection, comparing the number of deaths to the number of people currently infected can be a poor comparison, particularly if case numbers are growing rapidly. This is because those who currently have the disease may still either recover or die, and hence cannot yet be allocated properly into the fatality count. Rather than wait until all outcomes are known, one approximate adjustment has been to compare deaths to reported cases two weeks prior, reflecting the estimated median time between reporting and death. As of 12 May, 97 people in Australia have died with COVID-19, and there were 6,545 reported cases two weeks prior to that, giving a case fatality rate of 1.5%.

True differences in fatality rates

There are some very real differences that mean fatality rates could differ widely across countries. These include:

Age and risk profile of the population and those infected. People aged 80 and over are at a far greater risk of dying from COVID-19 than other age groups, so the proportion of people aged over 80 is a key factor. In China it’s 2%, in Australia it’s 4%, while in Italy and Germany 7% of the population are aged 80 or over. Equally, who contracts the disease matters. In most countries, the proportion of people contracting the virus has been relatively flat across adult age groups, with the occasional ‘spike’ for those aged in their 20s and 30s. But if widespread infection occurs in older age groups, via nursing homes and residential aged care settings for example, the effects can be devastating.

A good analysis of how other risk factors like co-morbidities, gender and ethnicity might influence fatality rates is included in an article from a group of life insurance actuaries in the Actuaries Institute’s Pandemic Resource Centre.

Health system response. If treatment is unavailable, the results can be tragic. In Daegu in South Korea, some patients died at home waiting to be admitted to already full hospital beds; case fatality rates in hard-hit Wuhan were six times higher than other parts of China. Triage guidelines had to be released in Italy to help doctors ration the use of ventilators and it’s argued that this is one reason deaths amongst older people were so high. Putting that into the Australian context, around 10% of cases in Australia have required hospitalisation and roughly 2% were admitted to an ICU, at least half of whom required ventilation. Health departments have worked hard to increase ICU capacity to some 7,000 beds. But if the virus was allowed to spread through the community until we achieved some level of herd immunity, that might mean 60% of Australians contracting the virus, around 180,000 deaths from COVID-19, over 1.2 million people needing hospitalisation and 240,000 needing treatment in an ICU. It’s easy to envisage a situation where the health system is overwhelmed and death rates soar.

Better treatments in future. The Medical Journal of Australia reports that over 500 randomised control trials are underway to find treatments for COVID-19, and these may reduce fatalities. For example, an early trial of the antiviral drug Remdesivir has shown a statistically significant reduction in recovery times and a small (though not statistically significant) reduction in fatalities. Larger trials of this and other treatments are in train to test their effectiveness.

So as we learn more about the virus, get major hot spots under control, and improve testing, reporting and treatment, we can expect to see some convergence of case fatality rates, and some of the very high rates seen in Europe, North America and elsewhere should start to fall.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.