Home insurance affordability and socioeconomic equity in a changing climate

The Actuaries Institute recently launched its latest Green Paper examining home insurance affordability and socioeconomic equity in a changing climate.

The paper, commissioned by the Institute and authored by actuaries Sharanjit Paddam, Calise Liu and Saroop Philip of Finity Consulting, represents an important contribution to the discussion around the availability and affordability of home insurance in an era of climate change.

|

Sharanjit Paddam and Calise Liu joined the Actuaries Institute podcast to discuss the key points of the Green Paper. Listen below or click here. |

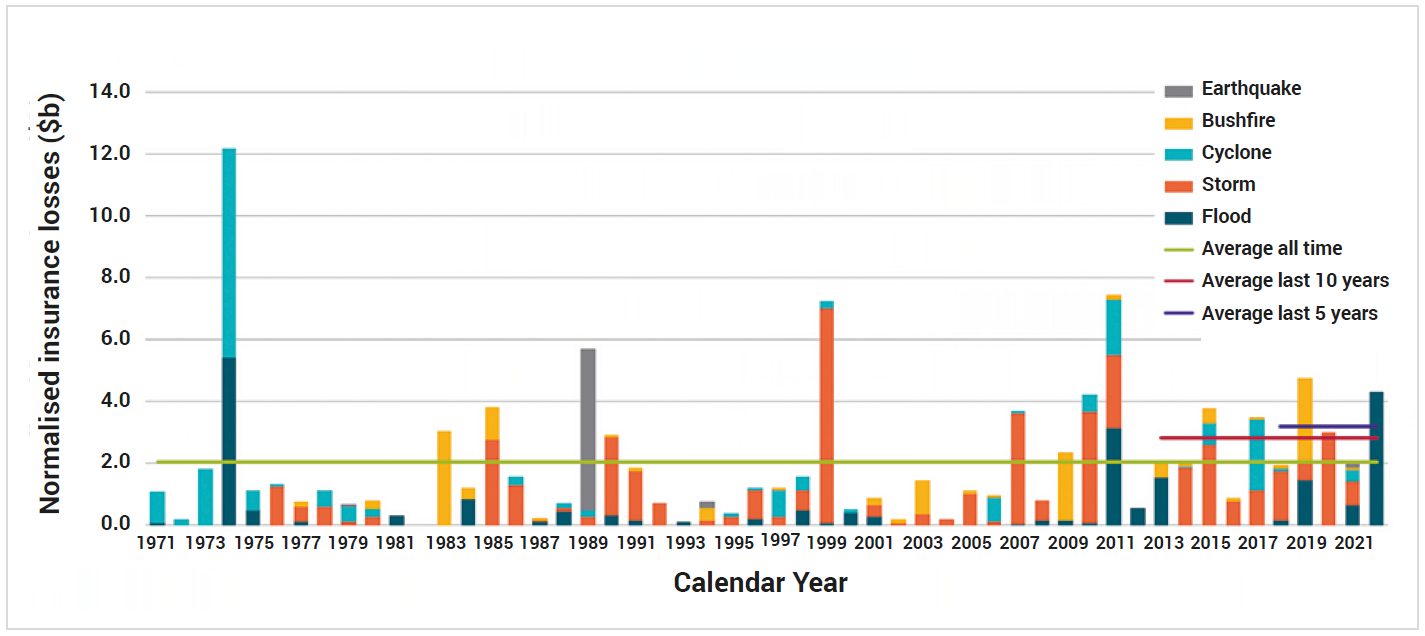

Home insurance losses have increased over recent years compared to long-run historical averages, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 – Historical insurance losses in Australia

This, combined with a more sophisticated techniques and more granular data becoming available, has resulted in significant increases to some home insurance premiums, with larger increases for households that are more exposed to natural disasters.

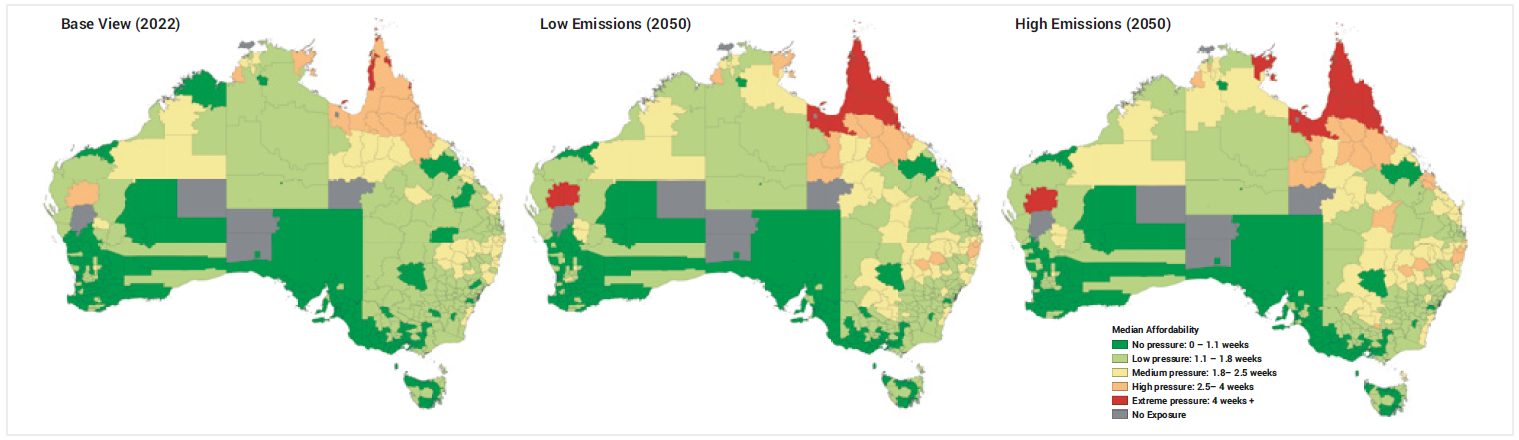

Drawing on earlier Institute research about home insurance affordability, the Institute has created the Australian Actuaries Home Insurance Affordability Index (AAHIA). Those households where the AAHIA is four weeks or greater are banded as under extreme pressure, and called vulnerable households.

This latest paper also overlays each of a low and high emissions scenario of climate change to project what affordability by household may look like in 2050.

While the median Australian household spends 1.1 weeks of gross income to pay a median annual home insurance premium of around $1,500, this varies widely according to geographic location.

Figure 5.2 shows that the one million households with AAHIA exceeding four weeks of gross income are concentrated in Northern QLD and the Northern Territory.

Figure 5.2 – Median AAHIA as at 2022 and under low and high emission climate scenarios

In Northern NSW and Northern QLD, lower household incomes and higher cyclone, flood and bushfire risks contribute to affordability pressure.

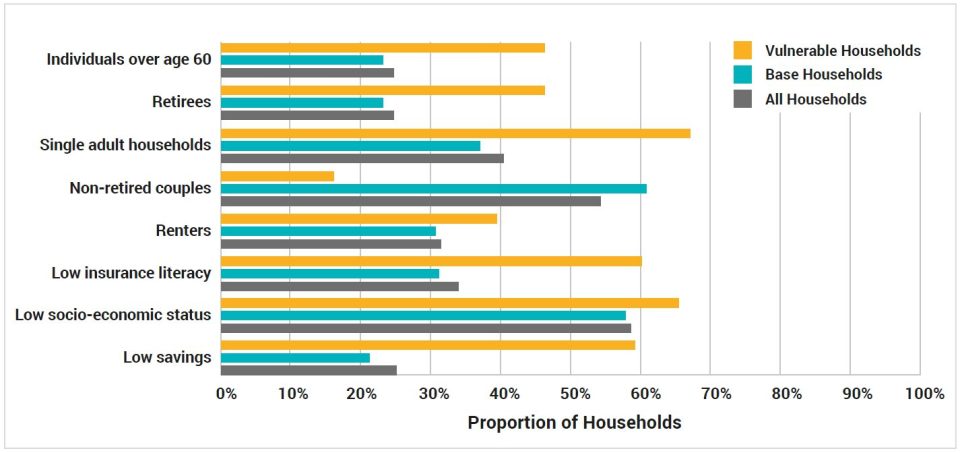

Figure 1.2 demonstrates the clear differences between these vulnerable households and remaining households (base households) that experience no to high affordability pressure.

Figure 1.2 – Population characteristics of vulnerable and base households

These one million households are likely to be older, retired, renting, lone adult or single parent households, with lower insurance literacy contributing to a lack of insurance coverage, and having lower current saving balances.

The paper makes it clear that the impacts of climate change will be far greater on these vulnerable households compared to base households under the climate scenarios that have been considered in the paper.

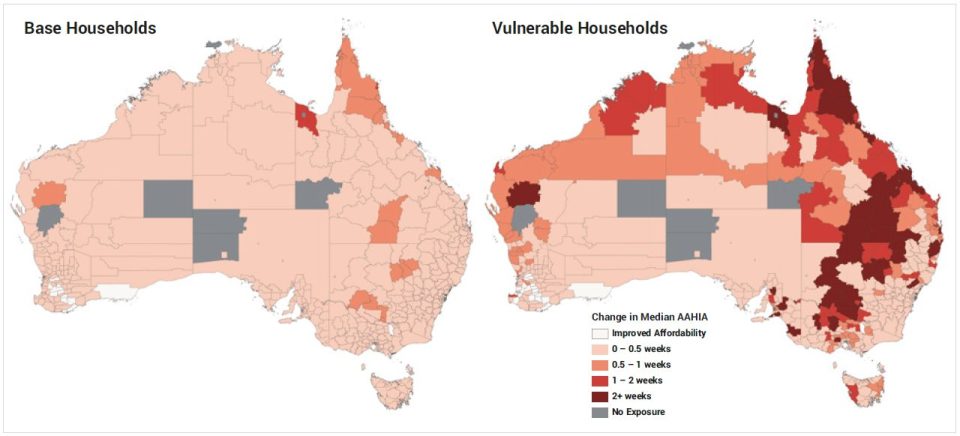

Under the climate scenarios considered in the paper, the majority of the base households – concentrated in the major population urban centres – will see increases in home insurance affordability pressure of up to half a week of income, as shown in Figure 1.3. But vulnerable households will experience larger increases in insurance affordability pressure. Northern Australia, other parts of QLD and Central NSW will see significant increases in pressure.

Figure 1.3 – Increase in median AAHIA under a high emissions scenario

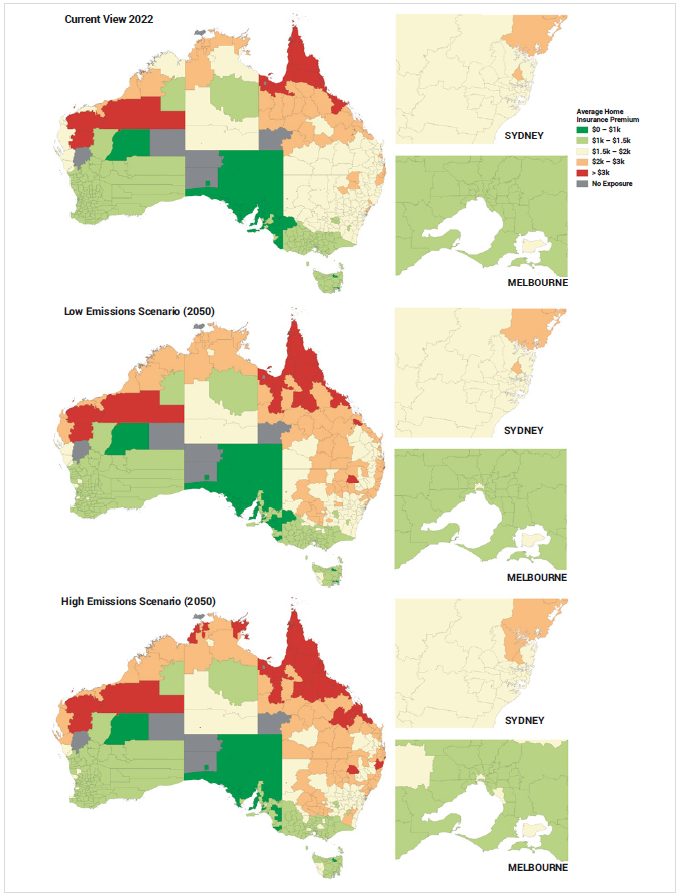

Average annual home insurance premiums across Australia have been considered in the paper under both low emission and high emission scenarios. In Figure 4.3, the number of Local Government Areas currently facing average premiums of $2000-$3000, and higher, are concentrated in Northern QLD. However, those areas will spread throughout most of QLD, and into NSW, as well across Northern Australia, under a low emissions scenario. Under a high emissions scenario, nearly all of QLD, Northern Australia and large areas of NSW will face significantly higher premiums.

Figure 4.3 – Mean annual home insurance premium by LGA – current, low and high emissions scenario ($2022 values)

Other figures in the paper break down expected premium changes according to bushfire, cyclone, and flood risk.

Disaster risk management now recognises that disasters only occur when natural hazards and vulnerable populations intersect. Economic, planning and socioeconomic decisions will alter the community’s vulnerability to the impact of cyclones, floods and storms.

The paper thus sets out nine recommendations to address home insurance affordability and rising socioeconomic inequity of climate change. Strong collaboration will be required between policymakers from all levels of government for these actions to be effective, as well as assistance from insurers and banks, builders and developers, First Nations Australians. Effective implementation will require consultation with homeowners.

A priority should be investment in resilience measures to address home insurance affordability pressure.

Factors such as protective infrastructure, land use planning and building codes, access to goods and services, governance, emergency relief levels, and clean up, recovery and rebuild, all contribute to resilience.

This long-term investment in resilience can reduce home insurance premiums and improve the availability of insurance cover, reducing non-insurance costs for government, emergency services and care organisations, and households.

For example, mitigation infrastructure such as the Roma flood levees in QLD, costed at an initial $28 million, has resulted in $130 million in avoided damage, and restored insurance availability.

Past land planning and building standards have contributed to the impact and severity of disasters, as communities can assume that building approvals imply the area is safe for residents, leading to households underestimating potential risks. Some of these communities have faced multiple flooding events and extensive repair and rebuild costs, funded partly by taxpayers.

Better building standards and land use and planning changes in local government could reduce inequity by avoiding development in high-risk areas like flood zones.

Changes to the building code should recognise the increasing likelihood of severe weather events, and consider the value of protecting property assets as well as protecting life. Stronger standards will increase community resilience.

Some areas cannot adequately manage the losses from persistent severe weather events, and managed retreats should be considered in those situations, as have happened in flood-prone areas like Bega (1851), Clermont (1916), Grantham (2013) and others.

A cost-benefit analysis over the long term shows managed retreats can provide better value than other resilience options, and planning frameworks should be advanced for this purpose. However, homeowners must be sufficiently engaged and their awareness of risks raised for relocations to be successful.

Following a series of investigations into insurance affordability, most recently the Northern Australia Insurance Inquiry, the Federal Government elected to create a cyclone reinsurance pool, backed by a $10 billion government guarantee. Based on work from Finity Consulting, Figure 6.1 shows that the pool could reduce cyclone insurance premiums for high-risk households by 38%, and 28% for medium-risk households.

The Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation has included reductions in premiums for households that undergo cyclone mitigation measures, and this could address the need for adaptation and resilience.

While the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission monitors insurers to see that savings on reinsurance costs are passed to consumers, the Government should regularly monitor the efficacy of the pool over time. For example, if the scheme has incentivised households to increase the resilience of their homes to cyclone risk.

Retrofitting homes to withstand stronger cyclones can limit the impact of damage, and raising homes above the flood line can contribute to flood-proofing properties. However, their long-term effectiveness depends on whether expected climate change impacts are taken into account.

The paper also recommends exploring options to subsidise home insurance for lower-income and vulnerable households, at a more targeted level.

The cyclone reinsurance pool is a systemic wide policy that risks being a less efficient and effective solution compared to direct subsidies to vulnerable households.

State-based stamp duty and levies have a compounding effect on those already facing higher insurance premiums, exacerbating home insurance affordability pressure. Multiple reviews have found insurance taxes are inefficient and should be replaced with alternative revenue sources. The Paper suggests that the removal of all tax charges would reduce the median AAHIA across Australia from 1.1 weeks to 0.9 weeks, and for vulnerable households from 7.4 weeks to 6.6 weeks.

Another recommendation is to improve policy making through better information on natural hazards and the impact of climate change. Australia currently lags behind other jurisdictions in this space.

Better information provided through a public central database should help address home insurance affordability, with a range of measures suggested in the areas of more publicly available current vulnerability data for buildings and infrastructure, updated flood hazard maps across Australia, embedded climate risk considerations in land use and planning, and including insurance affordability in broader housing affordability such as that measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Currently, central government databases do not include home insurance premiums in the assessment of housing affordability, while insurers themselves do not have access to an adequately detailed industry database to accurately assess mitigation measures undertaken by household and reflect risk across the country.

Improvements in data accessibility will improve household awareness of disaster and insurance risk, and help to better identify vulnerable households.

With this, governments can create better policy, resource and recovery planning, emergency planning and risk assessment.

Furthermore, a national strategy should be created to address resilience in existing infrastructure and develop a priority list of resilience-building projects. This should include implications for building codes where building vulnerability to natural hazard is changing.

It is also beneficial to consider nature-based solutions to adaptation and mitigation, and in this area First Nations Australians should be consulted for their extensive knowledge of the Australian landscape. Such solutions could include soft-landscape areas in built environments to replicate natural water cycle management, thereby reducing flooding, or planning forests and mangroves which can also provide carbon storage solutions.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every podcast listened to.