Powerful storytelling

Saliya Jinadasa reflects on the power of the story for improving communication and what he learnt on a recent training course.

I have heard and read articles about the importance of storytelling in presentations. Some of the famous people are great storytellers. Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, is one such example. He epitomises storytelling. His stories on his early failures are fascinating. His story of being the only person rejected out of 24 applicants for a KFC job is particularly memorable..

Part of my role is regularly presenting to C-suite clients and senior management. I was curious and wanted to know more about how storytelling can be incorporated into the analytics work that I do. After all, stories help us to make sense of the world.

Happily that opportunity arose recently when the Singapore Actuarial Society organised a one-day training course on ‘Powerful Storytelling’. I had no hesitation in signing up. To add icing to the cake, the course was heavily subsidised. At the end of the course I felt that the money and time spent was one of my best investments.

Due to prevailing COVID-19 restrictions, the training was conducted online via Zoom. There were 12 participants. The instructor was great, showed lot of enthusiasm and used his personal stories along the way.

One of the lessons was that content and word choice mattered in only 7% for the success of a presentation. Body language and voice tone mattered far more. As actuaries who love to talk about numbers this seems shocking. However, when I reflect on my work, there is always a key message to convey with our numbers. If we can identify that messange, then the challenge is using a personal story to link to the key message we want to convey with numbers.

I learned that stories enable us to remember concepts, ideas and information and allow us to put ourselves in other people’s shoes and see their perspective. When a personal story is simple, relatable, genuine and has a climax, it grabs attention and tends to stay with listeners. A personal story does not have to be a grand story. It could be a simple life event but with a meaningful or powerful message in it. Your story can be from art, music, friendships, vacations, sports or hobbies; whatever builds that personal message.

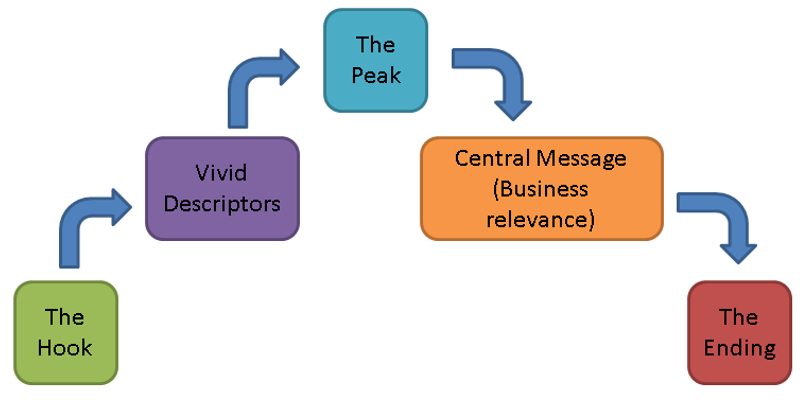

The course introduced a structured framework, with five main steps: a hook, vivid descriptors, a peak, a central message (business relevance) and an ending. The instructor compared these steps to climbing of a mountain.

The Hook

The opening statement designed to grab listener’s attention and pull them into the story. A good hook can be provocative, memorable, funny and can hint what is to come next.

For example, the instructor told a story about his summer vacations in his native England. He started by saying “I hated my mother”. We were straightway hooked into the story. He went on to explain that his mother had aerophobia and as a result his holidays were confined to England. However, he looked at it positively for creating pleasant memories for him with summer vacations.

Vivid descriptors

The story should make use of descriptions of sounds, emotions, visuals and smell. They should be used throughout the story to engage with five senses of the listeners.

The instructor vividly described his summer vacations being cold and windy and how his father put up windbreakers using cloths, sticks and stones at the beach.

The Peak

The Peak is the climax of the story. An effective peak should be obvious to the listener. A story should only have one peak.

The instructor talked about rock pools created by low tides in the beach and how he and his sister explored rock pools to find sea creatures underneath rocks to their excitement.

Central message

The Central Message is delivered soon after the peak and reveals the intended purpose of the story. It explains why the presenter chose this particular story to tell.

The business context was that someone was about to leave the company and the instructor was having a conversation with that person. He linked the peak of his story on exploring rock pools to the central message of looking for new opportunities within the company.

The Ending

An effective story ends quickly after the Central Message has been successfully delivered and makes it obvious to the listener the story has come to an end.

The story ended asking the person to consider opportunities within the company and the instructor being there to help.

Even though the ordering of the steps above feels natural, developing a story does not necessarily follow the same sequence. In the training, first we identified a business context. Second, we raked through our memories to come up with a story from past personal events. Then the story building process followed with Vivid descriptors, creating the Peak, and determining the Central message. Finally, we created the Hook.

My main takeaways from the training were:

- Storytelling is powerful. People remember stories, not necessarily content in a presentation.

- Your personal story does not have to be grand. It can be a simple event that has a meaningful or powerful message.

- A structured framework can help you to build a personal story with a central message and link it to a business context.

The next challenge for me is to put what I learned into practice and see whether it improves the effectiveness of my presentations.

Special Note: Author would like to thank Mudit Gupta (FIAA) for reviewing the article.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.