Where have all the higher maths students gone?

A fundamental problem in Australia’s education system is that maths subjects are being deprioritised in high school education. There are several contributing factors, and the adverse implications for individuals, our profession, and society, in general, are serious.

Participation Rate

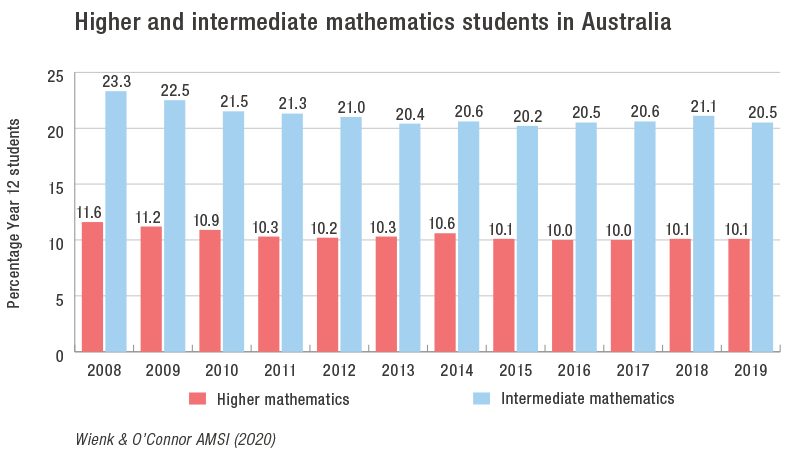

Participation in intermediate and advanced maths courses in Australia in Year 12 is very low and has declined over time[i]:

Whilst the proportion may have stabilised in recent years, it is alarming that only around 30% of Australian Year 12 students are studying intermediate or higher mathematics, compared with 35% in 2008. Whilst directly comparable figures are hard to obtain, the corresponding figure was around 47% as recently as 1998[ii].

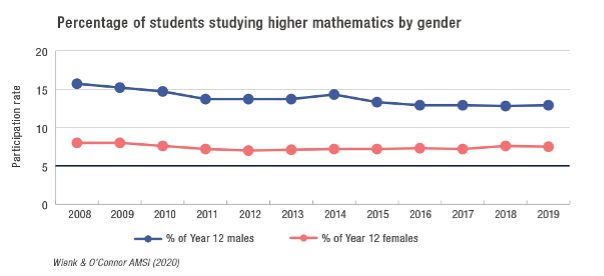

Of great concern is the disparity of the experience between males and females:

Only approximately 7% of Australian female students in Year 12 study higher maths subjects, compared with around 12% for males. Again, the proportion may have stabilised in the last 10 years. However, these low levels are not an encouraging sign for Australia’s maths professions.

School curriculum in Australia is primarily a state government responsibility, and there are significant discrepancies between the states’ education systems. For example, mathematics is not compulsory in Year 12 in NSW, ACT and Victoria, creating a situation where an increasing proportion of students in Australia’s most populated states are not studying any maths subjects in their final years of school.

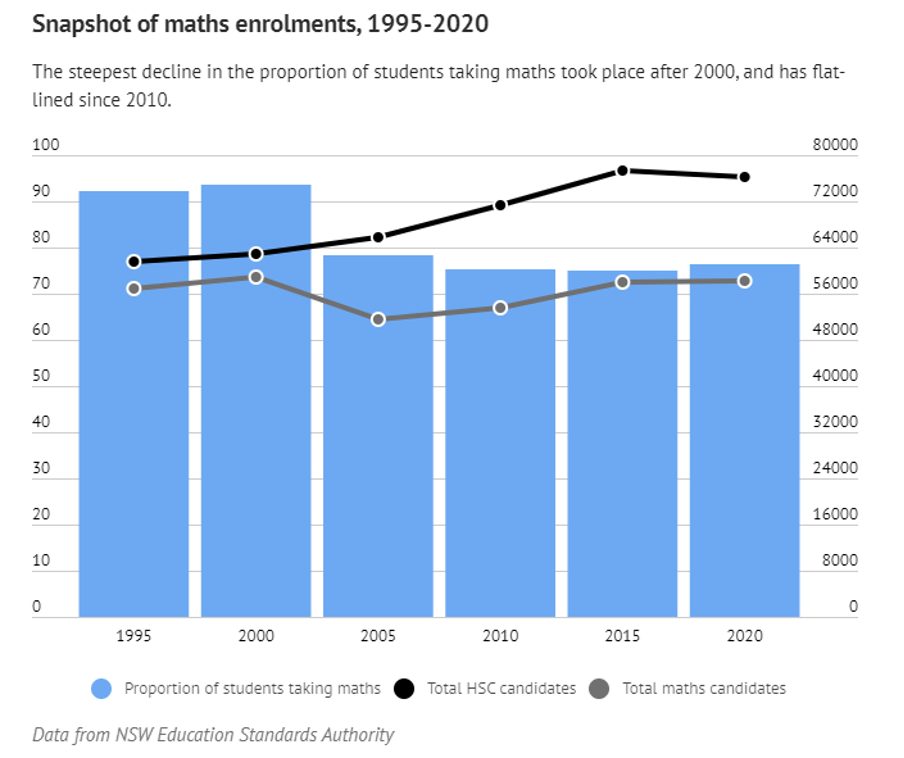

It is disappointing that as many as 25% of Year 12 students in NSW are not studying any mathematics in Year 12[iii]. While some mathematics remains compulsory in the final years of high school in some states and the International Baccalaureate program, this compares poorly with most OECD countries where it is mandatory to study mathematics in the final years of high school.

What is driving this phenomenon?

Many students are deliberately choosing not to study higher maths subjects. “Kids only choose subjects they know they’ll be successful in,” says Dr Sue Thomson from the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER)[iv]. Mastering mathematics requires students to memorise formulas and processes, including complex and sequential equations, and understand maths strategies to build a solid maths foundation. In order to learn, mathematics requires making lots of mistakes. Students must repeat the same types of questions until they master maths fluency, which can be a frustrating process. Repetitively getting the wrong answer may affect a student’s confidence, resulting in decreased participation.

Some students regard mathematics as abstract and irrelevant, with complex concepts to grasp, and they have difficulty connecting mathematics to real-life situations. Students’ preconceptions may also contribute to maths anxiety, where the student anticipates difficulty and creates blocks to prevent further learning and understanding of maths concepts.

Dr Thomson said, “Another reason is that when senior students are focused on excelling in standardised testing and achieving a high ATAR score, students may be encouraged to drop higher maths subjects to reduce the risk of a low score, including their cohort’s performance”.

A further factor may stem from how mathematics is assessed and graded in comparison with other subjects. For example, English, or text-based subjects like history, are assessed with various subjective factors such as creativity and style, with marks awarded for spelling and punctuation. However, maths assessments present few opportunities to earn subjective marks despite considering workings before the correct or incorrect answer is derived. This factor has potential benefits, of course, but students who lack confidence in their maths ability may not recognise them.

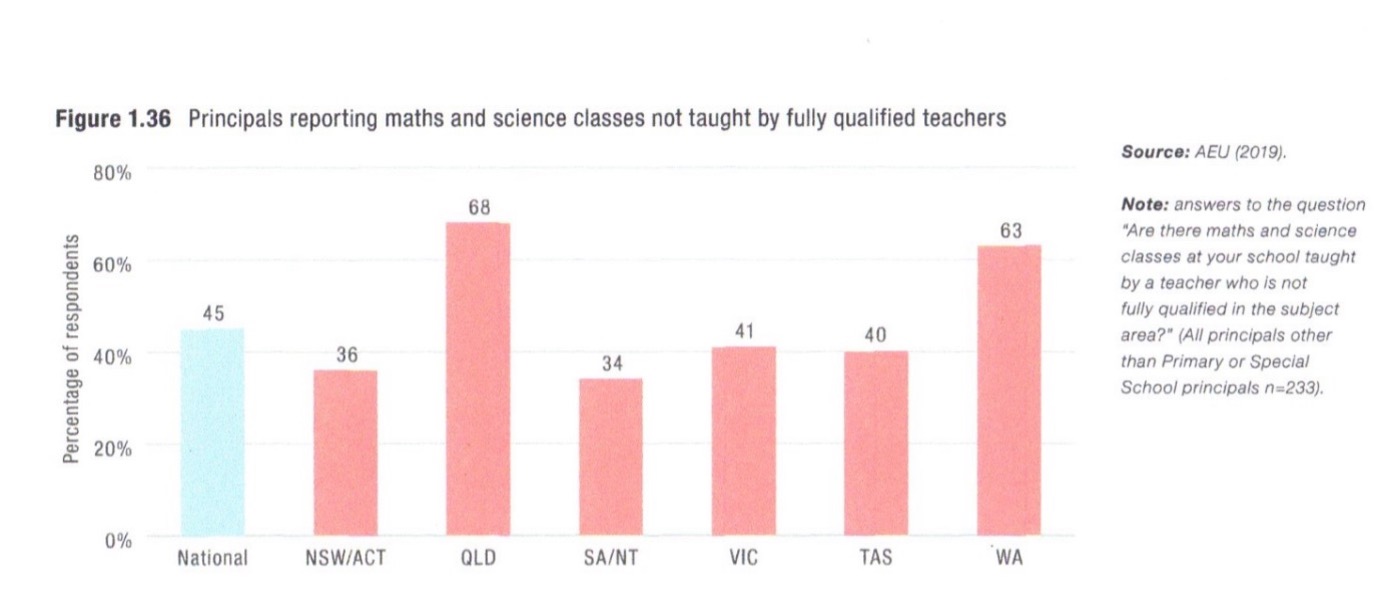

Dr Thomson also said a shortage of STEM-qualified teachers in high schools contributes to declining enrollment in higher-level maths and science subjects. The following chart provides some insight into the extent of the problem across Australia[v]:

A final factor is that many universities have removed mathematics as a prerequisite for degrees such as science, engineering, and commerce. This decision may have resulted from a decline in the number of students choosing to study advanced mathematics in high school, with insufficient numbers of students achieving adequate qualification for those courses. However, removing higher-level mathematics as a prerequisite for mathematics and science-based tertiary course means that there is even less incentive to study advanced maths courses in high school.

Are these enrolment trends a pattern or a problem?

Society is constantly changing, so it makes sense that today’s education sector looks different to the past. However, as a profession that relies on mathematics and analytical understanding, the decline in higher maths participation is detrimental, both individually and for society.

Navigating life requires a foundation of mathematical understanding. A simple example is when consumers need basic mathematics to assess value when price and quantity are different. Maths skills are also required to understand interest calculations for loans (or deposits) and returns on investments. As adults, we all need to interact with financial concepts at some stage in our lives. Higher stakes examples arise when large amounts of money are involved, like home mortgages, superannuation, investments, and insurance coverage. Maths skills help ordinary consumers make informed choices.

Even actuaries use only a small proportion of the mathematical techniques we studied at school. Conics, trigonometry, circle geometry, complex numbers … there is a long list of topics we do not regularly use in our professional careers. However, the key to studying higher mathematics is that it teaches ordered, critical and creative thinking. Keith Devlin calls it ‘deep learning’[vi], whereby students find logical and creative ways to draw on what they already know to solve new problems. Regardless of the career that is chosen, these skills are inherently valuable and key to societal advancement.

Mathematically astute workers are highly valued and generously compensated, which should incentivise graduates entering the workforce. A 2016 Flinders University study[vii] indicates the extent of the salary premium for STEM qualified employees. For roles defined as “managers”, STEM qualified employees earn 10% more than non-STEM qualified employees. Even in roles classified as “Non-STEM technicians and trades”, the premium is 13%. STEM skills will be in increasingly high demand in the future as data analytics, technology, the digital economy, and financial markets expand[viii]. The consequences of declining higher maths participation in school will be far-reaching. Participation in higher maths study is lower for girls than boys and performance in mathematics is lower in low socioeconomic (SES) communities than high SES communities[ix]. Hence, school level mathematics study may perpetuate systemic inequalities that policymakers are addressing in other areas.

The current school maths curriculum may also exacerbate systemic inequality. It does not address learning styles or access to supporting resources available to some students when classroom-based maths learning is insufficient. Conversely, a targeted increase in maths participation in all schools has a role in providing equality of opportunity later in life. There is currently a significant appreciation of diversity in Australia’s workforce, and we should give Australian students the best maths education across Australia’s diverse education system.

Actuaries have first-hand experience with data interpretation, data visualisation and insight. However, people without these skills are left vulnerable when presented with impessive charts. Data analysis that is prepared to work towards a particular agenda may leave people with an inadequate understanding of mathematics and statistics open to manipulation.

What’s Next?

Australia, like our profession, benefits when deep understanding of maths becomes a solid outcome of Australia’s education curriculum. The Institute is calling on our members to join this discussion and volunteer with the “Financial Literacy and Higher Maths Working Group” to formulate a policy position statement calling on policy change and adding the Institute’s voice to this critical issue.

The working group will have the positive intent of providing constructive input as several government bodies examine curriculum and other changes. The Institute wants Australia’s students to be engaged in maths to deliver graduates with analytical and maths competency to Australia’s industries to compete in the global marketplace. We will highlight the current problems with Australia’s participation in higher maths across our education system and recommend material change to the education system.

A strong foundation in mathematics has many benefits for society. Please express your interest in contributing to the Working Group as it commences further work by emailing Clare Hughes: Clare.Hughes@actuaries.asn.au

Read the Media Release |

|

[i] https://amsi.org.au/?publications=year-12-mathematics-participation-in-australia-2008-2019 [ii] Kennedy, J., Lyons, T. & Quinn, F. (2014). The continuing decline of science and mathematics enrolments in Australian high schools. Teaching Science: The Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association, 60(2), 34-46 [iv] https://www.smh.com.au/education/hsc-students-abandoning-high-level-subjects-20180323-p4z5yn.html [v] https://amsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/amsi-discipline-profile-2020.pdf [vi] https://profkeithdevlin.org/; Mathematics is a way of thinking – how can we best teach it? [vii] National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University, Tom Karmel and David Carroll [viii] https://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/australias_stem_workforce_-_final.pdf [ix] https://amsi.org.au/The state of Mathematical Sciences 2020 |

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.