Actuaries Digital

The peer-reviewed platform where actuaries share evidence-based perspectives on the financial, social and technological issues of today and tomorrow.

This month in Actuaries Digital

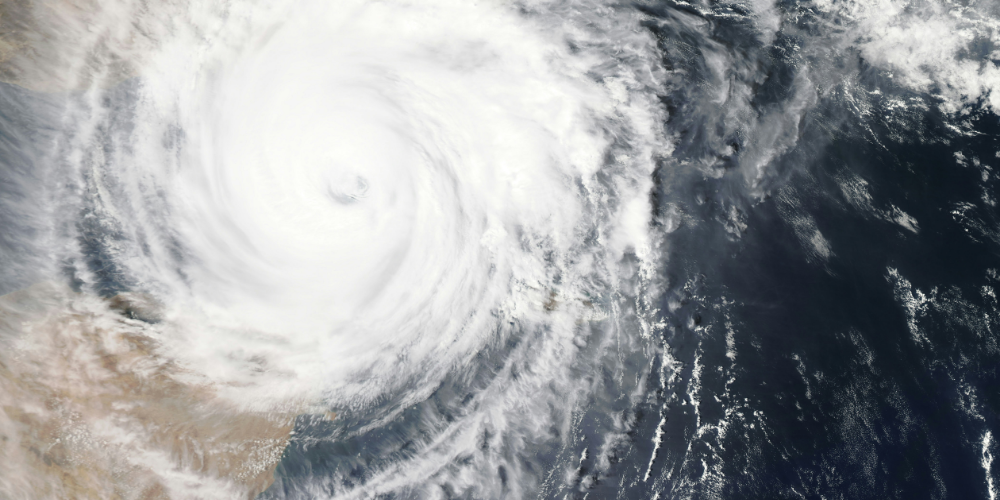

Reinsurance Explained: A Pillar of Strength for General Insurancers

A Dialogue Paper providing a comprehensive outline of reinsurance, the insurance bought by insurers to protect against major losses.

Trending topics

In conversation

Podcasts and videos

Meet the Actuaries Digital editorial team

The informative and inspiring articles published on Actuaries Digital are overseen by our editorial team, subject matter experts within our membership who dedicate their time and expertise to bring actuarial insight to current and emerging topics and challenges.

Lead the conversation. Contribute to Actuaries Digital.

We’re always looking for new research, fresh perspectives and candid conversations. Share your ideas with our editorial team today and you could be published in Actuaries Digital.